Category — prison

The Experts

Do you know who the experts are in “sheltering* in place”?

The 2.3 million men, women and children currently warehoused in our prisons, jails and youth facilities.

They know what lock-down means.

They know what social isolation means.

They know what social distancing means.

They know what it is like to live without access to restaurants, coffeehouses, bars, libraries, movie theatres, museums, retail stores.

They know what rationed health care means.

They know what rationed toilet paper means.

They know cabin fever.

They know fear of others.

They know dread, angst, uncertainty

This is their lives. Every. Day.

*If you can call the concrete cages they live in “shelter.”

March 25, 2020 2 Comments

Tears

Today I made two people cry.

No I didn’t tell them bad news. No I didn’t yell at them.

In fact, the opposite.

I told one man that he was a talented writer, that the stories he had to tell were very much worth telling. We were sitting across from each other in the penitentiary’s visiting room. He is 37, convicted of aggravated murder and serving a sentence of life without parole. There are many other things to know about this man, some that will scare you, some that will crack open your heart. But what I want to tell you now is that when I told him how I felt about his abilities, he looked down at the floor and was silent for a long moment. When he looked up, his eyes were brimming with tears.

“I don’t cry,” he said. “I don’t ever cry.”

He said it had been a long time since someone believed in him, that he no longer believed in himself.

A few hours later I was helping to serve meals at Food for Lane County’s innovative Dining Room—not a soup kitchen but a service-at-the-table, cloth-napkin restaurant-style venue that feeds as many 300 hungry people a day. A woman at one of my tables had finished eating and was sitting, staring into space. It was not a dreamy stare. She sat like that for close to ten minutes, almost motionless. I asked if she was okay, if there was anything she needed.

She looked at me hard, like she was trying to remember if she knew me (no) and then if she wanted to engage with a stranger (yes).

“I was taught to trust people,” she told me. “But they take advantage of that. They see I trust and they use that.”

A woman living on the streets, living on the edge. Of course she is right to be cautious, to protect herself, to present as less vulnerable than she feels, than she is. I didn’t know what to say. But I had to say something.

“I hear you,” told her. “I understand as well as I am able to. But I have to tell you, I think most people are good. Most people are good.”

‘I want to believe that,” she said. “I wish I could believe that,” she said. “I no longer believe that,” she said. And then she cried.

March 11, 2020 No Comments

Women’s Work

Women’s Work is a powerful, stunning book that chronicles–in extraordinary photographs and inspiring text–the lives and work of more than sixty women. They are funeral directors and firefighters, pig farmers and blacksmiths, pilot and cowgirls, ranch owners, gold miners, beekeepers. I am honored to be included. People are always saying/ writing about how they are “honored” to be included or mentioned or to have won something. This is the common parlance of the so-called Humble Brag that we see on Facebook, which I hope you despise as much as I do.

So let me explain the sincerity of my being “honored.” The photographer whose vision—intellectual, cultural, artistic—shaped this book is an exceptional talent, the kind of talent that does not have to announce itself, that works quietly and intensely and humbly. Being in his presence, being the object of his gaze for this photo shoot was the first honor. (We had worked together several years before when he flew west to do a photo shoot for Prevention magazine story I wrote.)

The other honor is the more obvious one: These women! Their energy, their boldness, their perseverance, their commitment. The authority in their faces. The strength of their bodies. To be in the their midst empowers me. I was selected not because my work as a writer breaks gender stereotypes but because of my work teaching writing in a maximum security penitentiary to convicted murderers and my book chronicling the lives they live inside.

The photography is all Chris Crisman’s. The accompanying text is written by the women themselves. I think the mix is a wham-bang.

About my image: It was made on the grounds of Oregon State Penitentiary, just to the right of the entrance. We had hoped to shoot inside, or at least by the release gate, but that was not to be. My time inside, including close to one hundred writing group sessions with the men over a period for four years, was often filled with humor. But I did not want to smile for this photograph. Prison is a hostile, toxic environment. Those who survive, those who change and transform—like many of the writers I worked with—do so despite not because of their years of punishment. This is what is uplifting and energizing: these stories of transformation.

March 4, 2020 2 Comments

Compassionate release

Compassionate release.

Virtually all state prison systems and the federal prison system allow for the early “compassionate release” of sick, elderly, or disabled prisoners. Almost always, this doesn’t happen.

Now comes Bernie Madoff, the financial world’s equivalent of a serial killer. Entering the final stages of kidney disease with less than 18 months to live, he filed for compassionate release from federal prison. The Bureau of Prisons denied his petition, as it does 94 percent of those filed by incarcerated people. He has filed an appeal with the sentencing court.

Should he be released to die at home? Should we feel compassion for him? Here’s what a thoughtful New York Times opinion piece has to say.

I don’t think it’s a matter of feeling compassion—defined as “sympathetic pity and concern for the sufferings of others–for Madoff or for others seeking to spend their final days outside a prison. To feel compassion for someone who ruined so many lives may be beyond us.

But what is not beyond us is a long, long overdue public discussion about whether retribution should be our only penological aim, and justice for victims defined only as the long-term warehousing of perpetrators. Are victims made whole? Are criminals reformed? What does—what should–“justice” mean?

What do you think?

(And oh, the irony of this Times column just as Trump announces his list of commutations and pardons.)

February 19, 2020 4 Comments

Life inside

“Life Inside” is a monthly column about, well, life inside—“inside” meaning inside prison, within the walls of a maximum security penitentiary, behind a 25-foot concrete perimeter wall, behind the bars of a 6’x8’ cell. The column is written by the men in my Lifers’ Writing group, men serving life sentences, some of whom have lived their entire adult lives inside, some of whom will never get out.

“Life Inside” is a monthly column about, well, life inside—“inside” meaning inside prison, within the walls of a maximum security penitentiary, behind a 25-foot concrete perimeter wall, behind the bars of a 6’x8’ cell. The column is written by the men in my Lifers’ Writing group, men serving life sentences, some of whom have lived their entire adult lives inside, some of whom will never get out.

What I’ve learned from these men, what I hope others reading the columns in Eugene Weekly will learn, is that there is life inside, that the drive to make a life—a life of meaning and purpose—transcends where we are, or even who we are. These men live in the most restrictive and darkest of places. They live in a toxic environment: chronic stress, everyday hostility, incessant noise, no privacy, poor food, lack of connection to the natural environment, limited opportunities to maintain family ties, mind-numbing routines. And yet they don’t just survive (although this is, to me, astonishing in itself). They work on restorative justice programs within the prison, reach out to at-risk youth, volunteer as hospice workers or crisis counselors, join therapeutic or service-oriented groups, take classes, commit time and energy to a writers’ group, bake cookies to put in holiday gift bags for fellow inmates. Get married.

My hope is that my book, A Grip of Time, and now these columns, help others to see what I have seen and learned during the past four years: That these guys are human beings, that they should not be defined by (and we should not look at them through the lens of) the single worst moment in their lives. This does not mean being “soft on crime.” It does not mean that we shouldn’t hold wrong-doers accountable for their wrong-doing. It means recognizing the human being.

Oddly, or maybe not so oddly, this is also a lesson I learned when, as research for a previous book, I embedded myself in another dark, restrictive world, the world inhabited by those with Alzheimer’s. Before I spent months working at a residential facility for those with this disease, I viewed people with dementia as empty shells. Because they had lost their memory, I assumed they had lost themselves. The self. I assumed there was no there there. Not true. Even without access to their pasts, they still lived a life. They took pleasure in food, in music, in touch. They made friends and enemies, got angry, laughed.

The life they lived was not like our lives, just as the life the imprisoned men lead is not like our lives. But it is lived. Often fully, Often with meaning and purpose. If we recognize this, we can see them as the human beings they are.

(Illustration by Liza Mana Burns)

January 22, 2020 5 Comments

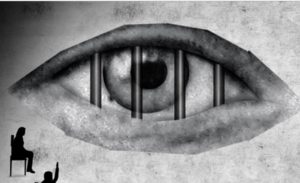

Statistics are PEOPLE

Statistics can be numbing.

I am asking you to un-numb yourself for a moment. To let these numbers sink in. To realize that behind these statistics, embedded in these numbers, are real people.

They are living out their lives both behind bars and in our communities.

I will continue to tell their stories. You need to continue to care. And to take action.

>The United States has the largest prison population in the world. We are home to five percent of the world’s population and nearly 25 percent of all prisoners.

>We have the highest per capita incarceration rate on the planet. In 2018 in the US, there were 698 people incarcerated per 100,000.

>The female prison population has doubled since 1990.

>70 million people in the US have a criminal record.

>While violent and property crimes are down by half since their peak decades ago, annual admissions to jails have nearly doubled during the same time period.

>Serious mental illness affects one-in-six men and one-in-three women in jail.

>There are as many as 2.7 million children who have a parent who is incarcerated.

>One in three black men and one in six Latino men will serve time in prison during their lives.

January 8, 2020 2 Comments

Collatoral Damage

What is a holiday “gift” for a person behind bars?

For some families, “gift”-giving is not an isolated activity around the holidays or a birthday. It is a year-around commitment, a financial burden (usually shouldered by women) they can ill afford.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that the United States spends more than $80 billion each year to keep the U.S. prison population—the largest on the planet—behind bars. Many experts say that figure is a gross underestimate because it leaves out the many hidden costs that are often borne by prisoners and their loved ones. These costs rise during the holiday season, as families visit and call more, send more care packages.

The Prison Policy Initiative, an organization working to reduce mass incarceration, estimates that families spend $2.9 billion a year on commissary accounts and phone calls. I have written about both these issues here (commissary) and here (phone calls). Much inside our public prisons is privatized.

A New York Times article this Tuesday puts faces and personal stories to this issue.

There is Telita Hayes who adds nearly $200 to the commissary account for her ex-husband, incarcerated in the Louisiana State Penitentiary for the past 28 years. On top of the $2,161 she has put in his commissary account so far this year, Ms. Hayes has paid $3,586 in charges for talking to him on the phone when she cannot make the hour-long drive to the prison, and $419 for emails sent through the prison’s email system. Ms. Hayes said she spends an additional $200 on visits and phone calls around Christmastime.

Families are also often responsible for paying court fees, restitution and fines when a member goes to prison. According to a 2015 report by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, the average family paid roughly $13,000 in fines and fees.

The Times story goes on to detail the trade-offs families (everyone mentioned in the story is a woman) make to financially support the incarcerated lives of loved ones. These women struggle to pay their own bills. They go into debt. One reported that her car was repossessed for nonpayment.

Since the 2008 recession, when state legislatures looked for ways to bring down the rising cost of incarceration, these hidden costs to families have been rising, sometimes astronomically. Hadar Aviram, a professor at the University of California, Hastings College of the Law, quoted in the Times story says: “Public prisons are public only by name. These days, you pay for everything in prison.”

It is worth considering who we end up punishing when we sentence someone to prison. In war this is called “collateral damage.”

December 18, 2019 No Comments

Old behind bars

J, a guy in my writing group at the penitentiary, stopped coming to our bi-monthly workshop. I found out it was because he couldn’t climb the long flight of concrete stairs up to the second floor room where we held our sessions. He had diabetes. His foot had become infected. There were complications. He was 66. He had been in prison for 37 years.

M, another of the men in the writing group, also stopped showing up. I found out it was because he was bedridden in the prison’s infirmary after a knee-replacement operation. He was 59. He had been in prison for 30 years.

When we sentence wrong-doers to decades-long prison sentences, what happens is that—no surprise–they age in prison. That is, they become old behind bars. And they become older faster than the rest of us. It’s estimated that incarcerated people age about 15 years faster than we do. (Fifty-five is considered “elderly” in the world of incarceration. Medically, biologically, their 55 is our 70.)

It’s no surprise why prisoners age faster. They live in noisy, crowded, stressful, toxic environments with poor quality nutrition, limited physical exercise, poor sleep and no access to the natural world. They suffer the physical limitations and diseases that often come with age, including Alzheimer’s.

Right now there are more than 200,000 people aged 55 or older in our prisons. From 1999 to 2016, the number of people 55 or older in state and federal prisons increased 280 percent. By 2030 it’s estimated that 1 in 3 prisoners will be 50 or older.

Prisons were not built for or equipped to handle physically compromised people who cannot pull themselves up to the top bunk in a cell or climb up and down stairs or walk across vast expanses of institutionalized space to get to chow hall or the infirmary. They were not built for or equipped to handle those with cognitive issues like dementia.

One solution? Build geriatric prisons. The Kansas legislature will be considering a recommendation next month to renovate a prison to serve as a 250-bed geriatric care facility. Price tag: $9-10 million for renovations, $8.3 million per year for operations. Over the next decade, we could spend hundreds of millions of dollars remodeling and retrofitting prisons as nursing homes.

Or, how about this: We stop sentencing people to absurdly long prison terms.

Criminology research shows that lengthy terms actually have little effect on deterring crime. And that older prisoners pose very little, if any, threat to communities if released.

December 11, 2019 No Comments

Life Inside

This is NOT a “humble brag,” a concept I detest for what I humbly believe to be its gross insincerity. (As in: What a humbling experience it is to my humble self to have all this great stuff happen to me. Let me tell you just how great. But humbly. Puh-lease. Spare me.)

This is a BRAG, BRAG. I am unabashedly bragging about the men I have worked with for the past four years, all inmates at Oregon State Penitentiary. I am bragging—without an ounce of humility—because today Eugene Weekly launches a regular monthly column, Life Inside, which will feature essays written by these men. Readers will be transported inside the walls of a maximum security prison to learn about the everyday lives experienced by the men who, for decades, have called this place “home.”

Working with these men, helping them craft stories that reflect their experience, stories that empower them in a powerless place, stories that help give them voice when they had none…this has been the single most rewarding work I have ever done as a teacher or an editor.

These men all committed crimes, bad ones. None claim they were wrongly accused or convicted. What they do claim—now 20, 30, 35 years into their “grip of time” behind bars—is that they are human beings capable of growth and change. Of deep remorse. Maybe, even, of a kind of forgiveness. In one terrible moment they ruined lives: the lives of their victims, their victims’ families, the lives of their own families, of themselves. They know that. They live with that.

But they also just live. They eat and sleep and work. They make and lose friends. They visit with family. And now, they write. They want to be thought of, to be remembered, for something other than the worst thing they did.

I hope you will read their work, today and in the future.

I write this with deep gratitude to Camilla Mortenson, Eugene Weekly editor, and Anita Johnson, one of the paper’s owners, who embraced the idea of a monthly column. And I write with everlasting gratitude to OSP Recreation Specialist Steven Finster, who supported, with enthusiasm, compassion and never-say-die energy, the formation of the group.

To learn/read more about the writing group, the men, and what I learned from them, may I (humbly!) suggest my latest book, A Grip of Time: When prison is your life.

November 27, 2019 No Comments

Learn from the experts

We learn from experts, from those who know. They know because they have thought long and hard about the subject, because they’ve studied it. And sometimes, most powerfully, because they have lived it.

I am not an expert on prison life. But for the past four years I have learned from experts, from a group of men who have lived behind bars for twenty, twenty-five, thirty or more years. They are members of the Lifers’ Writing Group I started at Oregon State Penitentiary. They write powerfully, with humor, with heart, with courage, with regret, with confusion and with insight about their everyday lives: sleeping, eating, working, making and losing friends, getting married, sitting by the bedsides of the dying.

I tell some of the stories they have shared with me in my book, A Grip of Time. I have also helped them craft and polish their stories for submission. Two of these stories won national recognition in 2018 Pen America Prison Writing Contest. Two more won in 2019.

A number of shorter pieces appear on the site I created here. These stories are powerful, important and timely. They are a testament to how people can live lives of meaning and purpose in places designed to deaden meaning and eliminate purpose. They are a challenge to all of us to consider how people, people who have done bad things, might be human beings capable of growth and change.

These stories, written by experts, can help us learn about the criminal justice system we have created, the system that has made the United States the undisputed #1 jailer in the world.

I am so delighted that on Monday the Washington Post devoted an entire issue of its magazine to publishing personal stories, essays and art produced by those formerly or currently incarcerated. Let these stories, by the experts, help us non-experts have informed, humane conversations about crime and punishment, about incarceration and rehabilitation, and about the hidden lives lived by millions—yes, I said millions—of American citizens.

October 30, 2019 No Comments