Category — prison

Framing. Naming.

The postings, the “manifestos,” the random spewings that fueled the Buffalo rampage…This is hate speech: brutal, ugly and obvious. It vilifies. It targets. It ignites fear. It incites violence.

But there are more subtle ways of directing hostility and engendering fear. There is word choice, sometimes nuanced. There are what facts are included and in what order. This framing and naming can go unnoticed. But that does not mean it is without consequences.

Within about a week of each other, two substantial pieces of journalism appeared that focused on issues related to incarceration in Oregon. One was a long, meticulously documented investigation by a senior reporter for the Huffington Post. It was centered on Mark Wilson, a “jailhouse lawyer.” The other was a story in the Oregonian about an ongoing investigation into possible “financial discrepancies” in the oldest and largest prison club at Oregon State Penitentiary, the Lifers’ Unlimited Club.

In the HuffPost story, Mr. Wilson is introduced in the first paragraph as “a prominent incarcerated legal assistant with a near-perfect disciplinary record who has helped thousands of other prisoners pursue legal claims.” The work he has done is then detailed. In this story, we first discover what Mr. Wilson has made of his incarcerated life since his 1986 crime. Then, 12 paragraphs later, we learn that when “he was 18 and addicted to methamphetamine, he took part in a double homicide during a home burglary.” We know the crime. We know the context. But first we met the man.

The Oregonian story, is introduced with this headline: Prison club for Oregon’s convicted killers investigated

Many, but not all, of the members of the Lifers’ Unlimited Club are convicted killers. There are other reasons to be sentenced to life. Regardless, the article is not about the crimes any of the members committed 20, 30 or 40 years ago, it is about how the Club functions now. Who are the men in charge of the club? Did they do anything wrong managing the operation of the club? That is the question.

But when the reader is first introduced to the club treasurer, the very first thing we learn is that he was “convicted of aggravated murder in the beating death of…” Later, the editor of the club’s newsletter is introduced to us by several sentences detailing the crime he committed 34 years ago.

These crimes happened. These men are guilty. Absolutely. But how does knowing this before we know anything else about them affect our suspicions of their potential wrongdoing in club activities? Don’t we begin with bias? Conversely, how does learning about Mr. Wilson’s legal work first, rather than his crime first, affect how we view this man?

Ninety-five percent of everyone who is incarcerated in the US eventually get out. That includes most members of the Lifers’ Club. If we learn to see them only through the lens of their terrible past, if we identify them by the very worst thing they ever did, how can we not be afraid of them? How can we possibly welcome them back into our communities?

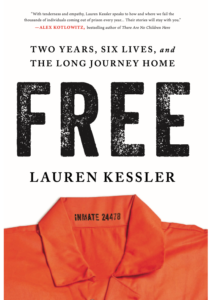

I hope you will read about the post-incarceration lives I chronicle in my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home. Is it possible to reclaim your life? Is it possible to do good after causing so much harm?

May 18, 2022 2 Comments

Strangers in a strange land

Don’t try to imagine what life is like for someone who lives a quarter of a century behind bars. You can’t. And Hollywood or Netflix will not help you.

Yet I need you to think about that person who has lived in a cell for 25 years, who has worn the same blue/green/orange uniform every day, who has learned to respond to bells, to a number rather than a name, who must scan an ID badge every time to enter or leave a room, who queues up for meals, for showers, for medications, for an hour or two outside, who stands in line to make a monitored phone call, that person who waits to be escorted to a room to see, at a prescribed time, a father, a mother, their child, that person whose life has been ruled by routine and circumscribed by surveillance, who has learned the wariness of a caged animal, who no longer remembers how to make a decision, that person who has internalized the powerlessness of this life.

The effect of decades behind bars, of all of the above and more—language, posture, intonation, emotional and psychological bandwidth–is called “prisonization.” It is the process by which inmates adapt to prison life by adopting the mores and customs of inmate subcultures. It is the socialization of inmates to the culture of prison because that is their culture and because adopting its norms keeps them much safer than not.

They become who they have to become.

And then, one day, the gate opens, and they are free. More than 600,000 men and women make the journey from caged to free every year. Ninety-five percent of people who spend time in prison eventually get out.

You cannot imagine their life inside, but you can imagine what meets them once they’re out–because that’s the world you and I inhabit. It is a chaotic, fast-paced, tech-heavy world filled with people who have also internalized their culture, who know the rules (and which ones can be blissfully ignored), who know that acting independently and taking action is often the good and right thing to do. It is a world that presents us with up to 35,000 “remotely conscious” decisions every day—more than 225 of them about food alone. And we take this in stride.

Those just out the gate are truly strangers in a strange land. Do you wonder how they handle the everyday turmoil we take for granted? Do you wonder how they make their way? Do you wonder what it takes to reclaim—to reimagine—your life after long-term incarceration?

The six people who let me into their lives as they traveled this path will help you understand. I hope you read their stories.

Image courtesy of Maria Fowler (beauty.and.her.books on IG)

April 20, 2022 4 Comments

Out of step, out of time

I met Belinda for the first time toward the end of her twenty-two-year stretch in prison. Back when she was eighteen she had been convicted of stabbing her pimp. She hadn’t meant to kill him, just hurt him. She’d been on the streets since she was fourteen, when her mother stopped the car and told her to get out, and she had learned to take care of herself. Or at least stay alive.

I saw her again the day she was released. It was raining that morning. She was wearing sweat pants a size too large and a cheap nylon jacket, clothes brought in by a friend the day before. She was lit up, like a girl rushing out to meet her prom date.

A month later, Belinda and I sat in a booth at a chain steakhouse where she ordered the most expensive item on the menu plus three extra sides. The food on the plates in front of her could have feed a family of four. Belinda hardly touched it. She had not looked up from her phone since we sat down. A month ago, she had never texted. A month ago she had never held a smartphone in her hand. Now she was nonstop-texting with her thumbs. She had gotten the phone three weeks before. She had acquired a boyfriend a week later. She was in the throes of what sociologists call “asynchronicity.”

While Belinda was in prison, her age cohort moved on. Inside, time was frozen. Outside, other young women acquired (and dumped) boyfriends or girlfriends, went to concerts, got (and lost) jobs, maybe went to college. On the outside, other young women moved to new apartments, new towns, new countries, had adventures, changed their look, had career aspirations that worked out or didn’t. On the outside, other young women grew into their thirties, found their place, lost it, reinvented themselves, settled in. They had children. Inside, Belinda had experienced a lot, but none of this. At forty, she was still in many ways a teenager. She was a teenager with a new phone texting a new boyfriend.

When we think about those being released from prison—that’s more than 600,000 men and women a year–we might wonder: Where will they live? Who will employ them? Will their families welcome them back? Will they end up back behind bars? But for those who have been away from the world for decades like Belinda, the questions are more nuanced. They are, in fact, existential: How will they recalibrate? How will they—out of step, out of time, out of place—find their footing, rejoin their cohort, make sense of their asynchronous lives?

In my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home, I ask these questions (and so many others) as I chronicle the reentry paths of six formerly incarcerated people, men and women, Black, brown and white, as young as thirty, as old as sixty. They allowed me into their complicated lives, alternately joyful and anxious, frenzied and stagnant—and for some, deeply asynchronous.

While Catherine was in prison—the youngest person to be tried as an adult for murder (she was thirteen)—she missed her adolescence, her teens, and her twenties. That may have fueled her marriage inside to a man she never was able to date; her quick connection, once released, to another man; her back-to-back pregnancies; her divorce. There was much catching up to do. She fast-tracked herself.

Trevor and Sterling went inside as teens, emerged as men. Vicki came back to children who had grown up without her. I hope you will want to read about their journeys, not only about the tough challenges and the uphill battles, but also and most especially about the extraordinary resilience that fueled (and continues to fuel) their journeys. I hope it makes you believe in second acts, in second chances.

(fyi: For every copy of Free sold between now and May 27 my publisher, Sourcebooks, will donate a book from their extensive catalog to Chicago Books for Women in Prison, a nonprofit that distributes books to prisons across the country. Purchase from anywhere.

April 13, 2022 4 Comments

Walking the talk

When I started going into prison to run a writers’ group for lifers, I wanted to help the men find their voices and tell their stories, and I also wanted to learn from them about the realities of incarcerated life, that hidden-from-view world inhabited by 2.3 million people in our country. As we talked about the art and craft of writing I kept suggesting books they could read that exemplified the power of nonfiction storytelling. None of those books were in the prison library.

But to be a writer one has to read good writing, yes? And to prepare for freedom one has to be able to practice (and hold dear) intellectual freedom: the opportunity to read books that open new worlds; the chance to write with clarity and passion about the world one currently inhabits.

During the three years the group met, I was able to bring in—volume by volume–quality books about writing techniques along with dozens and dozens of narrative nonfiction books culled from my own library and used bookstores. I had the extraordinary support of a prison staffer. The prison’s furniture shop created a tall wooden cabinet to house the “Writers’ Collection.” One of the men volunteered to be the lending librarian. We bragged about it shamelessly. And they read voraciously.

And now, thanks to a partnership between the publisher of my new book, FREE: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home, and the nonprofit Chicago Books to Women in Prison, I get to be involved in helping to build prison libraries on a national scale.

For every copy of FREE sold (it doesn’t matter from what retailer) between April 1 and May 27, Sourcebooks will donate a (different) book to Chicago Books to Women in Prison to distribute free of charge to state prisons in Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi and Ohio, as well as all federal prisons.

Their mission statement: “We are dedicated to offering the opportunity for self-empowerment, education and entertainment that reading provides.”

Because BOOKS CHANGE LIVES. (Which just happens to be the motto of my publisher.) And Sourcebooks walks the talk.

FREE is about how people reclaim and remake (and reimagine) their lives after long-term incarceration. I hope the stories I was privileged to tell give realistic hope to those who will someday be free. I hope these stories help families and friends and communities understand how freedom can be simultaneously joyful and overwhelming. I hope these stories bring into focus what it takes to help these folks be successful. What we need to do.

And now I get to hope a new hope: That with this partnership, my book, the sale of my book, will result in thousands of books donated to those behind bars. You can be part of this too.

April 6, 2022 4 Comments

I HEART librarians

As a writer, a reader, a bibliophile, one who believes that literacy unlocks countless doors, one who believes that books change lives, I have been a life-long lover of libraries. Especially public libraries.

Brief pause for historical interlude: As with many wonderful ideas that happened a long time ago in this country, Benjamin Franklin figures into the library narrative. He founded the first one in the colonies, a lending library in Philadelphia in 1703. The country’s first free (which is to say, tax supported) public library opened in the spring of 1833 in Petersborough, New Hampshire. The more famous (and erroneously claimed as “first’) Boston Public Library opened its doors in 1852. Fun fact: In the 1890s, the city boosters of Butte, Montana opened that city’s public library “as an antidote to the miners’ proclivity for drinking, whoring and gambling.” (One wonders how that worked out for them.)

A few years later, the millionaire (when that meant something) governor of New York, Samuel Tilden, bequeathed a fortune to establish the extraordinary New York Public Library. And then there was Andrew Carnegie, industrialist-philanthropist, who funded the establishment of more than 2,500 libraries worldwide, 1,689 of them, each a gem, in the U.S. Today, in case you’re interested, we have more than 16,000 public libraries.

And now, back to the present (or, rather, five days ago):

I am signing advance readers’ copies of my soon-to-be published book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home, at the Public Librarians Association annual convention. Sourcebooks, my extraordinary publisher (incidentally, the largest woman-owned publisher in North America) has a booth in the convention hall. There’s a line of librarians queuing up, the badges hanging from their necks identifying them as hailing from Alaska and Arkansas, Wyoming, Arizona, Louisiana, Denver, Boston, all over the Midwest.

In the thirty seconds or so I have to interact with each of them, I ask why they are interested in the book. I’m prepared for the usual answer: Adult nonfiction is a big category for us. I am not prepared for the personal responses: The references to family members or friends who have spent time behind bars and their difficult journeys back to their communities. And I am really not prepared to learn of their professional involvement, as librarians, in the lives of previously incarcerated in their communities.

These librarians see and talk with these folks every day. Some—far too many–who are released from prison are unhoused. On the streets at night, they find refuge during the day at the public library, a warm, dry place to sit, to read, to snooze. And yes, to use the bathroom. Some who are released go to temporary shelters or halfway houses or transitional housing, too often chaotic noisy places that can feel (and be) confusing or unsafe or both. A few hours of quietly sitting, undisturbed, in a public library is a respite.

The librarians I got to meet were on the frontline, aware of and sensitive to the challenges of reentry. More than a few talked about special programs they run or are creating to welcome and serve this population. “We are at the heart of our communities,” one Ohio woman told me. “We serve the entire community—and that means those who’ve spent time in jail and are now back home. We can model that for others.”

Oh librarians, how do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

The book I signed for them, the book you can pre-order now (publication date April 19):

March 30, 2022 19 Comments

On the plantation

The noise is deafening. In the cavernous “wet room” it is the churning of industrial washing machines. In the warehouse-sized “dry room” it is the whirr and whine of the dryers. With the fans blasting, the air is nonetheless hot, close, muggy. Like Georgia in late June. Like a plantation in Georgia in late June. The similarity only begins there.

I am describing Oregon’s second largest commercial laundry, a facility I toured a few years ago when researching and writing A Grip of Time. It is housed behind the 25-foot concrete wall that rings Oregon State Penitentiary and is one of more than two dozen businesses operated by a private entity within the Department of Corrections that manages labor contracts for the state’s prisons. Like those who labored in plantations in the South, the men who work in the laundry are slaves. Or at least indentured servants. Like plantation slaves, they are provided with (as one historian of the mid-1800s described it) “crude lodging, basic foods and cotton clothing.” The slaves of the South and the slaves within prison walls live in marginal conditions isolated with “their own kind,” working to support an economy they are not a part of.

Plantation slaves received no wages but could sometimes sell their services, after work, for nominal earnings that might equal as much as $100 a year. Prison laborers in Oregon are paid between 5 and 47 cents an hour. I’ll do the math for you:

$100 in 1860 has the purchasing power of $3,100 today.

The prison job, assuming 40 hours a week, 50 weeks a year at the top wage of 47 cents equals $977 a year.

The laundry work is low-level, menial labor that does not foster job skills useful to prisoners after release. The working conditions are unhealthy: loud enough so that earplugs are almost useless, the air in the “dry room” linty enough so that masks are required, the temperature hot enough so that everyone sweats all year.

Given all this, I should be overjoyed with the news that Oregon Health Sciences University, one of the laundry’s biggest clients, just announced that it is terminating its contract (in place since 1995).

Willamette Week reported it this way: Now, following a nationwide reckoning against racial injustice and demands for criminal justice reform, OHSU says the use of prison labor runs counter to its values. “The foundation on which our prison systems lie, and on which programs like laundry services operate, is antithetical to our values,” the president of OHSU said in a statement.

And, um, this conflict-of-values was just discovered after 25 years of supporting the laundry?

Still, I should be overjoyed, but here’s why I’m not.

Jobs in the laundry are actually considered the top jobs in the prison. They pay the most, offer two or sometimes three working shifts, are the only jobs to offer overtime, and are the only jobs to keep operating during lockdowns.

The men employed in these jobs, many of them, are trying to save money to show Parole Boards (and their families) that they are responsible. Or they are using these funds to pay for “luxury” canteen items like stamped envelopes so they can write to their families. Or an extra roll of toilet paper.

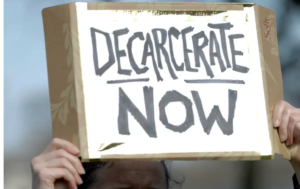

I am glad OHSU has decided prison labor runs counter to its values. Now how about we use this moment to examine the entire morally bankrupt system of mass caging of human beings that runs counter to OUR values?

July 1, 2020 2 Comments

The crisis is now

Isn’t it “under control?” Are we all just thrilled that our states and counties and cities are “opening up?” Are we looking forward to those summer parties? Making those summer travel plans? Because, you know: Flattening. The worse is behind us. Or, as the informed and deeply thoughtful members of the First Family tell us, the virus is about to “magically” disappear.

Regardless of what is happening in your community, in your state—and I hope the news is as good as it can be—please know this: Cases of the coronavirus in prisons and jails across the United States have soared in recent weeks. The number of prison inmates known to be infected has doubled during the past month. The Marshall Project reports that 46,967 prisoners have so far tested positive. Prison deaths tied to the coronavirus are up by 73 percent since mid-May.

Now, according to the national database maintained by the New York Times, the five largest known clusters of the virus in the United States are not at nursing homes or meatpacking plants, but inside correction institutions.

Of course they are.

We have heard for months that prisons and jails would be hot spots, that they are extreme high-risk environments.

They are often overcrowded, unsanitary places where social distancing is impractical, bathrooms and day rooms are shared by hundreds of inmates, and access to cleaning supplies is tightly controlled. Add to this that we have an aging (and chronically ill) prison population with limited access to health care. Oregon, my state, has one of the oldest incarcerated populations in the nation. Once behind bars, prisoners age faster than the rest of us. Health researchers estimate from 10 to 15 years faster.

The response from governors, from Departments of Corrections and from officials within prisons themselves has been inconsistent, muddled, mostly ineffective. A few states have moved forward with robust testing. Most states have not. Some states are releasing medically vulnerable prisoners; others are not. Many are stalling, arguing politics. This is not about politics. This is about health. Men and women are dying.

The crisis is now. The response must be now: testing for all; release not just for the medically vulnerable and aged but for all low-risk inmates who have served at least half of their sentences.

June 17, 2020 1 Comment

COVID behind bars

So here we are: masked, socially distanced, tending our sourdough starters. We are tracking the numbers: tested, infected, dead. We are tracking the phased, opening-up policies of our states: when can we get our teeth cleaned, our hair cut?

Meanwhile, in an alternate universe, 2.3 million people whose everyday lives are all about quarantine because they are serving time in jails and prisons, are getting sick.

At the end of last week, at least 20,119 people in prison had tested positive for COVID-19, a 39 percent increase from the week before.

The increase—and this is really just the beginning—is the result of the nature of the virus itself. (It is highly contagious and can be spread by asymptomatic people.) And it is the result of more aggressive and widespread testing within prisons. (A handful of states, including Ohio, Tennessee, Arkansas, Michigan, North Carolina began testing nearly everyone in prisons where people had become sick. The tests are coming back positive, hundreds of them.) And it is the result of the conditions within jails and prisons. (Not just overcrowded but populated by people who are less healthy with more “comorbidities” than the rest of us.)

Here’s what a report from The Marshall Project had to say: Unless the COVID-19 infections can be brought under control in jails and prisons, there is every reason to believe the outside (italics, mine) population will keep getting exposed to the virus as people in prison cycle back into society and as employees come home after being exposed to the virus. Only 11 states are releasing any data about how many prison staff workers have tested positive for COVID-19. Marshall calculated 6,100 prison and jail workers have tested positive for the coronavirus and at least 22 died. That, in all likelihood, is an underestimate of the actual number.

Here in my state, the first person who tested positive inside Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP) was a guard on one of the cell blocks. Last week, the DOC (Department of Corrections) reported 51 inmate cases in the state with 18 at OSP).

Today the report is 101 positives with 68 at OSP.

May 13, 2020 5 Comments

Life inside in the time of COVID

As of last night there were eight confirmed cases of covid-19 in Oregon prisons: three staff members at the Oregon State Penitentiary and three inmates and two staff members at Santiam Correctional Institution.

Everyone knew this was coming. And no one expects this will be the end. It is the beginning. Prisons are, in the words of public health experts, “petri dishes.”

On Monday, the Oregon Justice Resource Center along with two attorneys as co-counsel filed a class action suit against the Oregon Department of Corrections and Governor Kate Brown. The suit alleges that inmates’ rights are being violated by the “willful and/or deliberately indifferent medical care provided to them.” The seven members of the class action are all older than 60 and/ or have chronic health concerns that put them at additional risk.

This is from the Oregon Justice Resource Center’s announcement of the suit:

The plaintiffs are concerned that COVID-19 poses a serious risk to the health of all who live and work in Oregon’s prisons. There are many reasons why incarcerated people and those who work with them may be especially vulnerable to outbreaks of infection, including living at close quarters to one another, unsanitary conditions, poor health, and the large numbers of people who cycle through the system. Prisons are not built to adequately withstand a global pandemic; ODOC is not equipped or resourced to handle a public health crisis of this magnitude.

What’s happening inside? Here are three examples, according to first-hand information gathered by the OJRC:

An inmate in one prison became “very ill” with fever, dry cough, lethargy. He was denied a COVID-19 test. He was quarantined but still required to take his meals with the general population.

An inmate in another prison is housed in a dorm with 117 other women where the beds are three feet apart. Forty of the women have health conditions that put them at additional risk from COVID-19.

An inmate at another prison is on the hazard clean-up crew and has received to training or protective gear other than gloves. The disinfectant he is required to use is not an EPA-registered disinfectant effective against the virus that causes COVID-19.

Whatever is happening in our own stay at home/ mask up/ wash your hands lives, we might want to take a moment to think about the lives of the 2.3 million people incarcerated in American prisons and jails.

*Excerpt from a poem written by “Ted Point,” one of the men in my Lifers’ Writers Group at Oregon State Penitentiary

April 8, 2020 No Comments

Prisons and COVID-19

This morning began with the distressing—but completely expected—news of the first confirmed case of corona virus at an Oregon prison. The person is an employee at Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem, the state’s only max, where more than 2000 men live—most doubled-up in cells meant for one person, cells the size of your bathroom. This is the prison I know well, having spent more than four years as a volunteer there running a writers’ group for Lifers. I went in and out of that prison close to 100 times. I was there early last month visiting an inmate. Two days later, in response to the virus threat, the Department of Corrections closed all the prisons and jails in the state to visitors.

That was a smart move. However, as everyone familiar with this prison knows, OSP houses the state’s second largest commercial laundry, which receives thousands of tons of dirty linen from state hospitals and other institutions. It is unclear what precautions, if any, were taken in response to the threat.

But the virus entered the prison through an employee. With more than 4,500 people working for the Department of Corrections, many hundreds of them staffing three shifts at OSP, the virus has had so many opportunities to enter that it is surprising it took this long. The place is on lockdown as of this morning. That means everyone is confined to their cell 24/7 (except…if this lockdown is like the others…those inmates who work for the laundry).

In a letter to the director of the Department of Corrections, Colette Peters, officials with ACLU Oregon, the Oregon Justice Resource Center, Oregon Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, Partnership for Safety & Justice and Sponsors, Inc., asked her to reduce the prison population by considering people for early release.

“Given the mortality rate associated with the virus, we are concerned about the virus’s spread to at-risk people, particularly the elderly, within the closed confines of a prison setting,” they said in the letter. (Please see ACTION item at the bottom of this post.)

A 2012 study by the ACLU found that Oregon had the ninth-largest population of senior-aged prisoners in the United States, despite being only the 27th largest state by population. Research also shows that people in prison have higher rates of “co-morbidities,” those conditions (diabetes, heart disease, asthma) that make a person more vulnerable to the virus and far more likely to die from it.

If you have been tracking news about the virus and prisons, you know that Cook County Jail (Chicago) has recently reported at least 113 cases involving both inmates and staff. In the federal system, at least 52 inmates and prison workers across the U.S. have tested positive, including a cluster at the federal prison in Atlanta.

A worker there (speaking on condition of anonymity, fearing retaliation) made this point: “We do not have enough masks; we do not have the supplies needed to deal with this. We don’t have enough space to properly quarantine inmates.”

This would be true across ALL prisons and jails. These places where we warehouse 2.3 million people are, in the words of epidemiologists tracking the pandemic, “petri dishes.”

PROTECT OREGON INMATES FROM CORONAVIRUS (COVID19)

Please email, call, Tweet, mail

Governor Kate Brown:

Twitter @OregonGovBrown

900 Court Street, Suite 254, Salem, OR 97301, Phone: 503-378-4582

April 1, 2020 4 Comments