Category — Books

There is no me without you

There is no me without you.

There are no writers without readers. There are no writers without booksellers. There are no writers without librarians.

You make what I do possible.

And by “what I do,” I do not mean the act of writing. I make that possible. I mean the ability to reach people with my work.

I know, and have written many times and have told aspiring writers many times, “A real writer is one who really writes.” That’s from a Marge Piercy poem I can recite by heart. What she means is that publication is not what makes a writer a writer. Being a writer is defined by the way you see the world, the way you use writing to figure out that world, what’s important, what makes sense, what you think.

And Piercy may also have been alluding to the “flow state,” that time—minutes, hours if you are lucky—when you (the writer, the artist, the baker, the gardener, the athlete) are so divinely focused on the act of creation that you live outside of time, when all that exists in that moment is the doing. The “justification” for writing is writing.

But then, for me, there is being heard (read). There is hoping what I have discovered, what people have shown and told me, what I have come to understand might resonate, might spark questions and discussion and maybe even action.

And so, for me, readers, booksellers, librarians, arts and letters organizations, and gatherings like the one I was part of this past weekend matter. A lot.

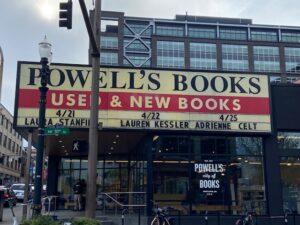

This past weekend I was one of four writers at GetLit at the Beach. No, not a writers’ retreat or a series of workshops. No, not a convention or highly orchestrated bookfest. It was instead a thoughtful, organized but somewhat freewheeling, high-energy three-day event designed for bibliophiles, the brainchild of Terry Brooks. That’s Terry Brooks, the fantasy fiction author with 23 New York Times bestsellers to his name. For the record, he is a self-effacing, down-to-earth, generous man, a sweetheart, actually.

And the event, from the opening reception on one of those glorious blue-sky days at the Oregon coast to the spirited closing panel discussion with rain pelting down (we were inside, of course), was…searching for words here: invigorating, empowering, exciting. Food for the soul. I left feeling proud–not of myself, but of the GetLit folks and Cannon Beach Book Company and the Tolovana Arts Colony and readers, readers, readers.

I am back, ready to work.

And the “me without you” begins with the support, encouragement, passion, perseverance and HARD WORK of Heather Jackson.

April 19, 2023 No Comments

What’s behind the curtain

No. I swear to you. This is not more self-promotion about the Oregon Book Award—although the life of the not-already-famous-with-massive-“platform”-writer (that would be me) has been overtaken by, swamped by, self-promotion. I wrote about this for Nieman Storyboard. And struggle with the tension between DOING the work and blabbing about the fact that I have done the work. And angsting about followers and likes and shares and reels and stories and how long I can ignore TikTok and what the New Big Thing will be that will suck up my time.

Instead, I want to pull back the curtain on what, to you all (not you writers reading this…you know the hard truth of this…) may look like “success.” I am talking about the (wonderful, gratifying) Oregon Book Award. Btw, that mention (now twice in two paragraphs) is good seo. For those of you blessed to not know what this is, it stands for Search Engine Optimization, the process of improving the quality and quantity of website traffic to a website or a web page from search engines. So, the more times I mention Oregon Book Award (see how I did that!), the better the chance that this little essay will show up when someone Googles that phrase.

Little man behind the curtain time. My experienced, smart, well connected, caring, and hard-working agent did not have an easy time finding a home for Free. It is not an easy sell. It is not an easy topic. Sure, people OUGHT to care. Sure, there SHOULD be ongoing community and national conversations about how to help people returning home from prison make meaningful lives for themselves. And, yes, the “low-hanging fruit” (criminal justice reformers and activists and the like-minded) may want to read a book like Free. But that, tragically—and I use that word advisedly—is a small group. So, a big publisher with clout and power in the literary marketplace was not going to embrace this book. And did not. It did not help that the previous book was about an even tougher-to-sell subject, life as it is lived by those who’ve been incarcerated for most of their lives.

The paperback. For my entire writing life, the paperback edition of a book follows the hardback by about a year. Standard. Paperback gives the book new life. Often paperback covers are redesigned to give a refresh. Book clubs love paperbacks and often wait for that edition. This publisher has no plans to publish a paperback edition until they sell more hardbacks. But hardbacks have a very limited life. Whatever promotion was done when the book was launched back in May of last year is it. And of course, there is the used book market, which kinda takes over after six months. That’s why paperbacks jump in to reinvigorate. Will the Oregon Book Award (yes, I did it again) make a difference? Who knows. And I don’t have the bandwidth to care as I direct my energies to my next book. What I do know this:

The real writer is one who really writes.

Work is its own cure.

You have to like it better than being loved.

(excerpted from a Marge Piercy poem)

Well, it’s nice to be loved too.

*image (mine) Packed house at Portland Center Stage/ Armory for Oregon Book Awards event April 3, 2023.

April 5, 2023 7 Comments

The author as relentless self-promoter

This essay appeared in Nieman Storyboard today. Click to see or read below.

It was the mid-1990s. I was sitting across a white damask table-clothed table at a midtown Manhattan steak house watching my editor, Bob Loomis, alternately cut into a ribeye and sip a dry Martini. This was it, and I didn’t even know it.

Loomis was then a septuagenarian, a very much living legend in the world of publishing, a man who had edited the likes of Maya Angelou, William Styron, and Calvin Trillin I didn’t know this at the time. I didn’t Google him because Google didn’t exist. I didn’t look him up in Wikipedia because there was no Wikipedia. What I knew is that I had a contract for my first book, “Stubborn Twig,” with Random House. What I knew was that an impressive older man in an expensive suit was taking me out for a pricey lunch and treating me like a was somebody.

In truth, I was nobody. So I put my shoulder to the wheel and wrote the hell out of the book, benefitting immensely from Bob Loomis’ frequent phone calls and quietly brilliant edits and queries (in pencil in the margins of my hard-copy manuscript). Three years later, when the book launched, it was greeted with reviews in more than a dozen newspapers. That was when so many newspapers had weekly book review sections. Meanwhile my publicity person sent me a multi-page itinerary that listed the bookstore events that had been arranged for me, along with my travel schedule, the hotels where I would stay and the names of the handlers that would be chauffeuring me around in each city.

All that, even though I was not a young, hot debut novelist. I was not a household word — even in my own household. I was simply getting the treatment that book authors got. I didn’t know it then, but I had gained entry to a world that would soon disappear. And my subsequent life as a writer would change in ways I could never have imagined back then and still struggle to imagine even as I am living that life.

The author as DIY marketing department

This is my life as a nonfiction author now:

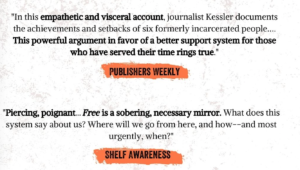

“Free: Two Years, Six lives and the Long Journey Home,” my eleventh book of narrative nonfiction, launched this spring. I have never met my editor in person. The only sustained conversation I have had with her was early on, pre-contract, when we were sussing out each other. Her Track Change notes and edits in Word.doc were fine but minimal.

This is not because I am now such a great writer that I no longer need a great editor. It is, I believe, because many of today’s editors have decades less experience than the editors of yesteryear, lower standards — I am now routinely praised for merely delivering a manuscript on deadline — and less time to devote to each project. My agent (a true gem and, not incidentally, an erstwhile “editor of yore”) offered the most insightful comments.

When the manuscript was in the process of becoming a book, I did what editors of yore used to take care of: I wrote the copy for the flap and back of the book. I went begging my writer friends for endorsement blurbs, followed up with near-desperate pleas, extracted pull-quotes from their generous responses, then compiled and sent these to the editor. I spent countless hours researching award-winning book covers, sending images, color palettes and type fonts to my editor. I took this on because I had learned that out-sourced illustrators had most often not read the book they were assigned to illustrate and had, as outsiders, not been part of any editorial discussions.

When it came to the title of the book, however, I lost the control I had always had. The marketing department took over. My agent and I had to mount a concerted effort to secure a title we could live with.

This extra work might be considered part of, or at least connected to, the writing process. But there is so much more to being an author now, and by “now” I mean for at least the last decade. For those who have visions of being the courted and cared for, that woman at the midtown Manhattan steakhouse, the cherished writer who flourishes within the brilliant, clever, commanding, and attentive world of commercial publishing: Sorry. No.

Blogs, tweets and favors from friends

What follows is a chronicle of some of the many responsibilities I — and most authors — shoulder today, the jobs we now must do, the tasks that fall to us if we want to see our work have a chance of success. If this sounds like whining, it sort of is. But as I whine, please know that I am conscious of the extraordinary privilege of voice. I am conscious of the privilege of being able to practice my craft, even if it means, as I heard a fellow journalist-turned-author lament the other day: relentless self-promotion.

The “cover reveal.” When the cover for the book was finalized — note my use of passive voice as there were three rounds of (to me) opaque market-testing going on that determined the final decision — it was time for me to start promoting the book. The book would not be published for months, but revealing the cover was an “opportunity” to gin up excitement and get people to pre-order. To be clear: I loved the cover. We, my agent and I, went to the mattresses (as Sonny Corleone put it) to get the cover we loved. But the point of revealing it (across all my social channels…more on this in a moment) was not to revel in the design but to offer a one-click option to pre-order. Pre-orders matter. A lot.

The blog slog. I created a book-centric blog back in 2011 when “My Teenage Werewolf: A Mother, A Daughter, A journey through the Thicket of Adolescence” was first published. I did this because, even after I was finished reporting and writing the book, my research into the mother-daughter relationship did not end. I wanted to share it. I did the same thing with my next book, “Counterclockwise,” which was my immersive investigation into the hope of the science of aging and the hype of the “anti-aging” movement. There was so much new research coming out and so much Internet-fueled garbage that I had to find a way to keep writing about the subject.

The blog slog. I created a book-centric blog back in 2011 when “My Teenage Werewolf: A Mother, A Daughter, A journey through the Thicket of Adolescence” was first published. I did this because, even after I was finished reporting and writing the book, my research into the mother-daughter relationship did not end. I wanted to share it. I did the same thing with my next book, “Counterclockwise,” which was my immersive investigation into the hope of the science of aging and the hype of the “anti-aging” movement. There was so much new research coming out and so much Internet-fueled garbage that I had to find a way to keep writing about the subject.

But all this subject-specific blogging was not, alas, helping to develop (and elevate) my platform, my (to quote from masterclass.com) “ability to market (my) work, using (my) overall visibility to reach a target audience of potential readers.” I was blogging to make new information available to those who might be interested. I was not blogging then to promote these books or to create a (Yes, I will use the B word. ) “brand” for myself.

Enter my now-branded blog (www.laurenchronicles.com) in which I labor to maintain my integrity while also creating thinly veiled promotional posts leading up to publication and during the important two to three months that follow. Because I am a writer who blogs and not a blogger who writes, I spend upwards of three hours crafting these 400-word posts, each a self-contained essay, ending with the implied or stated BUY THIS BOOK. I post links to the essay on my personal and author Facebook pages. I tweet it out. I try to figure out how to engage the largely visual audience that follows Instagram and mostly “likes” images of cats sunning themselves. Just in the last two weeks, I have spent more than a full workday creating reels for Instagram.

The maw of social media. I post. A lot. Much of it is book-related. I try — but I do not always succeed — to avoid those cringe-worthy “humble brag” posts ubiquitous on social media. (I am humbled by this glowing review of my new book… Humility? Really?) While I am on all these channels, I must pay close attention to such unwriterly but stunningly important things as optics, hashtags, SEO, followers, page views, bounce rate, device breakdown, referral sources. As part of my platform — without which I could not function in the book publishing world —I created and personally maintain and update my author site, my blogsite, my two Facebook accounts, my Twitter and Instagram feeds, my Amazon author page and my Goodreads page.

Is the tech stuff in my wheelhouse? Well, now it is. Does all this social-ing eat into reporting and writing time? You bet.

That’s why I was thrilled to hear that my “launch team” was going to play a big part in promoting my latest book. I heard this encouraging news during a three-hour webinar presented by my publisher. I have a team! I immediately jumped into chat to ask how I could connect with my team.

The self-launched team. It turns out that it was my responsibility to create this team by personally reaching out to friends, supporters, readers, my social media followers, anyone I knew who might be entreated to beat the drum for my book. I was to invite them to be “part of the team” and suggest different ways they could help: pre-ordering the book, posting pre-publication reviews on Goodreads, bombarding Amazon with five-star reviews the day after publication, liking my posts, sharing my posts, creating their own posts about my book, talking up my book to book groups or organizations they were part of. This would be ongoing communication. Every week I was to email my team with a new idea or a link to my new post or a review or interview that just came out or an announcement of a reading I was doing. I could, it was suggested, make little videos of myself talking excitedly about the book — a personal touch — and send these to the team.

Balancing the privilege and realities of authorship

And there is so much more that occupies me these days, including researching relevant podcasts and creating specific pitches for each; teaching myself how to produce reels for Instagram that are engaging but not silly or snarky; creating YouTube videos; immersing myself in TikTok (because #bookTok) to understand this Thing. And wishing that I was, instead, polishing the proposal for a new book. Wishing instead I was plunging ahead with research and reporting. Wishing I was living the life of a writer and not a self-promoter.

And yet, to live this (very privileged) authorial life, I must, like just about every other author today, spend a significant amount of my time not practicing my craft. Also, like possibly 98 percent of all book authors, I do not make a living wage from my books so must bolster my income and pay for my health insurance with teaching gigs and work-for-hire opportunities.

This is the reality for those of us who are not celebrities or “influencers,” those of us who do not have social media followers measured in the “Ks,” those of us whose life, work and thoughts do not go viral.

You know, we journalists. We who strive to tell important stories too big and too complex to fit into a newspaper article, or even a series. We who stubbornly dream about living the (vanished) life of the writer.

July 13, 2022 3 Comments

The Revolving Door

Get out of prison. Walk out the gate. Head over to the nearest 7-11. Rob it. Get caught. Go back inside.

Get out of prison. Walk out the gate. Go steal a car. Get caught. Go back inside

Recidivism, the rate at which former inmates run afoul of the law again, is one of the most commonly accepted measures of success (or, actually, failure) in our criminal justice system. The numbers are dismal. About three-quarters of inmates released from state prisons are rearrested within five years of their release.

But wait. Dig a little deeper—as researchers have done—and a far more nuanced picture emerges. For example: Most of the returns to prison in New York — 78 percent — were triggered not by fresh offenses but by parole violations, such as failing drug tests or skipping meetings with parole officers.

This is what the Marshall Project calls the Misleading Math of Recidivism.

When calculating recidivism rates, various states use different measures. Some states lump violating parole (technical violations like missing an appointment with a parole officer, failing to pay a restitution fine, failing to report travel), minor infractions that can trigger arrest (for example, a traffic violation, vagrancy), and committing a new crime as examples of recidivism. Other studies count only convictions for new crimes.

In other words, when we hear about the extraordinarily high rates of recidivism, we often don’t know what’s being counted. What we do know—what many people feel—is afraid. Let those bad folks out, and what do they do? They continue to be a threat to us and our communities. Keep ‘em inside. Throw away the key.

It is infinitely more helpful to think about (and question) those numbers in other ways:

What is being counted?

Why might there be so many parole violations? (Is parole overly punitive? Do parole officers have such excessive caseloads that they have no time to get to know their parolees and help them be successful? What are the most common violations and how can we restructure the demands of parole to mitigate this?)

And, most urgently and importantly, if prison is supposed to be about both punishment and rehabilitation, why is the rehabilitation component so weak (or nonexistent) that for some crimes—burglary and drug crimes top that list–there is, indeed, a revolving door.

Here’s surprising fact to chew on: The most violent prisoners are the least likely to end up back in jail.One percent of released killers ever murder a second time.

I hope you will want to read about the post-prison lives of six people—five of whom committed violent offenses and served decades inside, one with life-long addiction problems—in my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home.

None are back in prison.

June 1, 2022 7 Comments

The rocky road from caged to free

You’re like a ray of sunshine,” the interviewer told her. And she was. Just released after 17 years in prison, almost giddy with optimism and the promise of a new life, Catherine radiated energy and goodwill. She was focused, articulate, and charming. Her smile was infectious. She was confident but not arrogant, poised but not scripted, warm but entirely professional. Her buoyancy, which might have seemed almost adolescent, was tempered by her composure, a skill born of years navigating a life behind bars, of growing up and coming of age behind bars.

She was 30 years old, but for her this was the start of the life she was determined to live. Her résumé included a two-year college degree and a paralegal certification. Inside prison, she had designed and taught workshops for abused women. She wanted to be a teacher or perhaps a nurse. But first she had to establish herself, find a job that tapped into some of her skills and paid her accordingly so she could establish a work history and save for the future she dreamed of.

After the questioning and the conversation, after the smiles and the compliments, Catherine told the interviewer about her homicide conviction, a crime committed when she was just 13. The woman would find out anyway. Catherine thought that if she told the interviewer right then, in person, within the context of the interview that had just taken place, that person would see her in context. If instead her record was later uncovered during the background check almost all employers conducted these days, the interviewer would think she had tried to hide her past. Her crime, a violent crime, would stun them. They would, she figured, just toss her resume in the trash. So she told the interviewer that day. “We’ll call you,” the woman said.

Catherine, that “ray of sunshine,” waited for a call that never came.

How many interviews were just like that one? What job did Catherine finally get? How many years did it take for her to find the work that would change her life—and the lives of so many others?

I hope you’ll want to read her story, and the reentry stories of five others–their long journeys from caged to free–in my new book Free: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home.

May 25, 2022 No Comments

Why did I write this book?

Oregon author tells the stories of 6 people coming back to society from prison

By Amy Wang | The Oregonian/OregonLive

Eugene author Lauren Kessler sums up America’s approach to incarceration this way in her new book:

“We want those who have done harm to us to suffer, to pay for what they did,” she writes. “But in making them suffer, we create the kind of human beings we do not want back in our communities.”

Q: “Free” reads like a companion book for “A Grip of Time,” your 2019 book about men serving life sentences. How did you become interested in the subject of incarceration in the first place?

A: My general interest is these hidden subcultures in our midst that are peopled by, in this case, 2.3 million people that we know very little about…

If we have an epidemic of mass incarceration, then we also have the companion crisis of re-entry: 600,000 men and women coming back to our communities. Most of whom want to remake their life; they don’t want to go back. And so I wanted to know what that journey was like.

Q: If readers take away one thing from this book, what would you hope that would be?

A: So these men and women come back to our communities. We need to give them a chance to show us that they can be good citizens and community members. There are thousands in Oregon.

Other great questions include:

Q: Aside from housing and jobs, what facets of re-entry did you focus on and why?

Q: What were your thoughts about victims and their families and how they might respond to this book?

For the rest of the interview please click here.

May 11, 2022 No Comments

Walk a mile in my shoes

As they enter the basement of the church, each person is handed a folder with a name printed on it. It is not their name. It is the name of a fictitious person whose identity they will assume this evening. The people filing in are local business owners, teachers, cops, social workers, university students. They are here to participate in a simulation that will challenge them to complete the set of reentry tasks that routinely face those just released from prison. The fictitious people whose identities they will assume are men, women, Black, white and brown, short-timers who’ve been in and out of county jail, Lifers who spent three decades behind bars.

The biographies may be contrived for the purpose of tonight’s exercise, but the tasks are real-world. This evening’s simulation is a “walk a mile in my shoes” exercise that is both harrowing and instructive, an hour-long immersion designed to both foster empathy and spur community action.

In all the folders handed out this evening are documents detailing the conditions of the individual’s parole, from required check-ins to drug tests to mandatory treatments. And all contain a list of tasks to be completed. The participant-parolees will have one hour to complete these tasks. That hour represents one month—the first month—following release. The simulation is divided into four timed fifteen-minute/ one-week segments.

A whistle blows to begin week one. Clutching their folders, the ersatz parolees rush—or try to rush—from table to table. These tables line the perimeter of the room, each representing a different service, from the Department of Human Services to the Department of Motor Vehicles, from a community health clinic to a resale clothing store. There’s a rental agency, credit union, a parole office, a job center, a church, a payday paycheck cashing establishment. Alcoholics Anonymous has a table.

Should they get their SNAP food benefits first? Apply for health insurance? Maybe they should cash that small “gate check” they found in their folder? A few go to the credit union desk but find the minutes ticking away as they are asked to fill out lengthy forms. Others make their way to the paycheck cashing desk. When asked to present their ID to cash the check, several discover that the drivers’ license they were given in the folder has expired. They rush to the DMV table. But there is a long line there. And as they are waiting to get to the front of the line, the clock runs out.

The whistle blows ending the first segment. During that first “week” hardly anyone managed to check in with their parole officer. No one looked for a job. No one had time to go to the clinic to fill prescriptions for necessary medication. No one was able go to an AA meeting or attend mandatory treatment.

The whistle begins segment two.

If you would like to know how they fared in segment two, three and four, I invite you to read my new book, Free: Two years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home.

The simulation sets the stage for the reentry journeys of the six people you will meet, real folks, traveling the road from caged to free.

You will be amazed at the obstacles they face.

You will be more amazed at their resilience.

April 27, 2022 4 Comments

Strangers in a strange land

Don’t try to imagine what life is like for someone who lives a quarter of a century behind bars. You can’t. And Hollywood or Netflix will not help you.

Yet I need you to think about that person who has lived in a cell for 25 years, who has worn the same blue/green/orange uniform every day, who has learned to respond to bells, to a number rather than a name, who must scan an ID badge every time to enter or leave a room, who queues up for meals, for showers, for medications, for an hour or two outside, who stands in line to make a monitored phone call, that person who waits to be escorted to a room to see, at a prescribed time, a father, a mother, their child, that person whose life has been ruled by routine and circumscribed by surveillance, who has learned the wariness of a caged animal, who no longer remembers how to make a decision, that person who has internalized the powerlessness of this life.

The effect of decades behind bars, of all of the above and more—language, posture, intonation, emotional and psychological bandwidth–is called “prisonization.” It is the process by which inmates adapt to prison life by adopting the mores and customs of inmate subcultures. It is the socialization of inmates to the culture of prison because that is their culture and because adopting its norms keeps them much safer than not.

They become who they have to become.

And then, one day, the gate opens, and they are free. More than 600,000 men and women make the journey from caged to free every year. Ninety-five percent of people who spend time in prison eventually get out.

You cannot imagine their life inside, but you can imagine what meets them once they’re out–because that’s the world you and I inhabit. It is a chaotic, fast-paced, tech-heavy world filled with people who have also internalized their culture, who know the rules (and which ones can be blissfully ignored), who know that acting independently and taking action is often the good and right thing to do. It is a world that presents us with up to 35,000 “remotely conscious” decisions every day—more than 225 of them about food alone. And we take this in stride.

Those just out the gate are truly strangers in a strange land. Do you wonder how they handle the everyday turmoil we take for granted? Do you wonder how they make their way? Do you wonder what it takes to reclaim—to reimagine—your life after long-term incarceration?

The six people who let me into their lives as they traveled this path will help you understand. I hope you read their stories.

Image courtesy of Maria Fowler (beauty.and.her.books on IG)

April 20, 2022 4 Comments

Out of step, out of time

I met Belinda for the first time toward the end of her twenty-two-year stretch in prison. Back when she was eighteen she had been convicted of stabbing her pimp. She hadn’t meant to kill him, just hurt him. She’d been on the streets since she was fourteen, when her mother stopped the car and told her to get out, and she had learned to take care of herself. Or at least stay alive.

I saw her again the day she was released. It was raining that morning. She was wearing sweat pants a size too large and a cheap nylon jacket, clothes brought in by a friend the day before. She was lit up, like a girl rushing out to meet her prom date.

A month later, Belinda and I sat in a booth at a chain steakhouse where she ordered the most expensive item on the menu plus three extra sides. The food on the plates in front of her could have feed a family of four. Belinda hardly touched it. She had not looked up from her phone since we sat down. A month ago, she had never texted. A month ago she had never held a smartphone in her hand. Now she was nonstop-texting with her thumbs. She had gotten the phone three weeks before. She had acquired a boyfriend a week later. She was in the throes of what sociologists call “asynchronicity.”

While Belinda was in prison, her age cohort moved on. Inside, time was frozen. Outside, other young women acquired (and dumped) boyfriends or girlfriends, went to concerts, got (and lost) jobs, maybe went to college. On the outside, other young women moved to new apartments, new towns, new countries, had adventures, changed their look, had career aspirations that worked out or didn’t. On the outside, other young women grew into their thirties, found their place, lost it, reinvented themselves, settled in. They had children. Inside, Belinda had experienced a lot, but none of this. At forty, she was still in many ways a teenager. She was a teenager with a new phone texting a new boyfriend.

When we think about those being released from prison—that’s more than 600,000 men and women a year–we might wonder: Where will they live? Who will employ them? Will their families welcome them back? Will they end up back behind bars? But for those who have been away from the world for decades like Belinda, the questions are more nuanced. They are, in fact, existential: How will they recalibrate? How will they—out of step, out of time, out of place—find their footing, rejoin their cohort, make sense of their asynchronous lives?

In my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home, I ask these questions (and so many others) as I chronicle the reentry paths of six formerly incarcerated people, men and women, Black, brown and white, as young as thirty, as old as sixty. They allowed me into their complicated lives, alternately joyful and anxious, frenzied and stagnant—and for some, deeply asynchronous.

While Catherine was in prison—the youngest person to be tried as an adult for murder (she was thirteen)—she missed her adolescence, her teens, and her twenties. That may have fueled her marriage inside to a man she never was able to date; her quick connection, once released, to another man; her back-to-back pregnancies; her divorce. There was much catching up to do. She fast-tracked herself.

Trevor and Sterling went inside as teens, emerged as men. Vicki came back to children who had grown up without her. I hope you will want to read about their journeys, not only about the tough challenges and the uphill battles, but also and most especially about the extraordinary resilience that fueled (and continues to fuel) their journeys. I hope it makes you believe in second acts, in second chances.

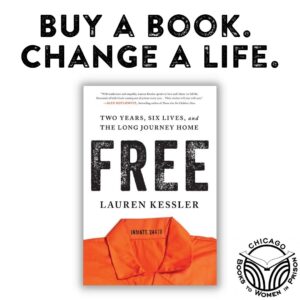

(fyi: For every copy of Free sold between now and May 27 my publisher, Sourcebooks, will donate a book from their extensive catalog to Chicago Books for Women in Prison, a nonprofit that distributes books to prisons across the country. Purchase from anywhere.

April 13, 2022 4 Comments

Walking the talk

When I started going into prison to run a writers’ group for lifers, I wanted to help the men find their voices and tell their stories, and I also wanted to learn from them about the realities of incarcerated life, that hidden-from-view world inhabited by 2.3 million people in our country. As we talked about the art and craft of writing I kept suggesting books they could read that exemplified the power of nonfiction storytelling. None of those books were in the prison library.

But to be a writer one has to read good writing, yes? And to prepare for freedom one has to be able to practice (and hold dear) intellectual freedom: the opportunity to read books that open new worlds; the chance to write with clarity and passion about the world one currently inhabits.

During the three years the group met, I was able to bring in—volume by volume–quality books about writing techniques along with dozens and dozens of narrative nonfiction books culled from my own library and used bookstores. I had the extraordinary support of a prison staffer. The prison’s furniture shop created a tall wooden cabinet to house the “Writers’ Collection.” One of the men volunteered to be the lending librarian. We bragged about it shamelessly. And they read voraciously.

And now, thanks to a partnership between the publisher of my new book, FREE: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home, and the nonprofit Chicago Books to Women in Prison, I get to be involved in helping to build prison libraries on a national scale.

For every copy of FREE sold (it doesn’t matter from what retailer) between April 1 and May 27, Sourcebooks will donate a (different) book to Chicago Books to Women in Prison to distribute free of charge to state prisons in Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi and Ohio, as well as all federal prisons.

Their mission statement: “We are dedicated to offering the opportunity for self-empowerment, education and entertainment that reading provides.”

Because BOOKS CHANGE LIVES. (Which just happens to be the motto of my publisher.) And Sourcebooks walks the talk.

FREE is about how people reclaim and remake (and reimagine) their lives after long-term incarceration. I hope the stories I was privileged to tell give realistic hope to those who will someday be free. I hope these stories help families and friends and communities understand how freedom can be simultaneously joyful and overwhelming. I hope these stories bring into focus what it takes to help these folks be successful. What we need to do.

And now I get to hope a new hope: That with this partnership, my book, the sale of my book, will result in thousands of books donated to those behind bars. You can be part of this too.

April 6, 2022 4 Comments