Everything changes

“Because I still matter,” one older woman said.

“Because I need to figure out what matters,” said a young man.

“Because I need time to think.”

“Because I think too much.”

There were maybe 30 of us pilgrims sitting on wooden chairs, crowded together in the little interior courtyard of the Iglesia de Santa Maria in Carrión. It was the late afternoon of my sixteenth day walking the Camino Francés. One of the four Augustinian nuns who would be leading us in song had asked us to say why we were on this journey.

“I need to do something to separate the life I’ve been living from the life that is now in front of me,” is what I said. “It needed to be something big.” There are so many moments on the Camino that grab hold of you, that surprise you, that sandblast you. This was one of those moments: Saying those words aloud, admitting the enormity of this transition, the blank canvas of the future. Being in the presence—and oh man, was it a presence– of these nuns, one of whom was so beatific that it was easy to imagine she had been touched by God. Even if you didn’t believe there was a God. Sitting in the fading sun with people from around the world, people you didn’t know but in that moment you knew intimately. Turning my head to see Kiki, our white hot friendship still in its early days, crying as we sang “Amazing Grace.”

And then the final song, the refrain of which went like this:

Todo cambió todo. Everything changes everything.

The song was lovely. But as I sang the words, I thought yeah, sure, I know this. Change is the only constant. The times they are a’ changin’. To exist is to change. Yep, got it.

But then I walked some more, a lot more, and a lot more after that. And I got home and slept in my own bed and made my solo dinners and stood here in front of this computer and did what I do. Then one afternoon I ventured out for coffee. Todo cambió todo.

“When you come out of the storm,

you won’t be the same person who walked in.

That’s what this storm’s all about.” ― Haruki Murakami

December 7, 2022 9 Comments

A landscape of kindness

“Choose to be kind” proclaim the wooden signs stuck in the lawns of every other front yard in my town.

I think about this a lot, about how performative “activism” (words, signs, t-shirts, bumperstickers) too often takes the place of real action, how they, in fact, excuse lack of action.

I thought about kindness a lot when I walked the Camino. Or rather, I didn’t think about it as much as I felt immersed in it, as much as I felt I was part of this landscape of kindness. One very hot afternoon, my favorite walking companion (and sister-from-another-mother) Kiki and I were trudging into yet another tiny village, Hornillos de Camino, on what was probably a 26 or 27 kilometer day. We were sweaty, dehydrated and cranky. We ventured into a mercado the size of a walk-in closet, each bought an icy-cold Kaz Lemón, and hunkered down on a log outside the store, sitting in the blazing sun. A minute later, the owner of the store appeared with an apple in each hand. “Manzanas cultivar en un huerto local,” he said, smiling and handing us the fruit. Then he insisted we move into the shade on a bench near his little store. That’s it. That’s not a lawn sign. That’s the real deal.

Another day, walking in the late morning with a soft-spoken Australian woman named Emily, we found ourselves winding down the steep cobblestone streets of a small village. I think it was Zuriain. It had been raining, misting really, and the stones were slick. We turned a corner and saw a small group gathered around a man sitting on the ground. When we got closer, we saw that his forehead was bleeding, and he had a gash across his nose. His left leg was outstretched, elevated on a pack. The ankle was wrapped. His toes were swollen and blue. He had slipped and fallen a few minutes before.

Brian, a nurse from Colorado whom I had met and walked with briefly the day before, had wrapped the ankle. Others walked with first-aid kits. He walked with a medical kit. Another pilgrim whose phone had a Spanish sim card had called an ambulance. It would take a while to get here. A third was speaking to the man’s wife in the Netherlands. Emily and I stood there for a moment. Then she walked over to his side, kneeled and took his hand. Just held his hand.

As I write this, I am reliving the moment. I am again part of this landscape of kindness: The rain starting in earnest; the small group gathered; the man, a stranger to all, in the center. And Emily, wordless, holding his hand.

Just fall into that for a moment, my friends.

November 30, 2022 4 Comments

Everything weighs something

It didn’t occur to me until the fourth day of walking the Camino when my (ever-so-carefully-chosen) super-lightweight backpack with its (ever-so-carefully-chosen) super-lightweight contents started to cause a deep bone ache in my left shoulder blade. I was unpleasantly—painfully—surprised. I had spent a lot of time thinking about and researching what to take on this 500-mile journey. I paid strict attention to grams and ounces, choosing a rain jacket I didn’t really like that much over one I did because it weighed two ounces less. I bought an ultra-light sleeping bag that closed with little plastic snaps rather than a weighty (as in 3.5 oz.) zipper.

I was relentless, obsessive. I parceled out three band-aids for my first aid kit instead of including a small box. I cut my toothbrush in half. Oh yes I did. Every individual item I chose to put in that backpack–everything I firmly believed (or was told on countless helpful websites) I would need for the journey—I chose by weight.

But…everything weights something. And all those somethings add up. All those somethings, together, were a big something. This came as an ah-ha moment four days in. It doesn’t sound like much of a revelation. But it felt like one to me as I wrapped the shoulder strap of my backpack in the moleskin I was carrying to treat the blisters I never got.

One of the things about walking every day for fifteen, eighteen, occasionally twenty miles—and then getting up and doing it again, and again, for 36 days—is that the monotony of the physical act frees you to think big thoughts. (Or sometimes no thoughts at all. )

And so, when “everything weighs something” popped into my head, I began to think big thoughts, like: Okay, this is not just about the damned backpack. It is about life. About the weight we carry. All those little somethings.

Sure, we are aware of the burden when something big happens: disease, death, divorce. That is heavy luggage. But we are often unaware of the collective weight of the many little things. That thing we should have said but didn’t. That thing we said but shouldn’t have. That misunderstanding that was never cleared up. That time someone disappointed us. That time we disappointed someone. That time we needed a little help and didn’t get it. That time we needed a little help and didn’t ask for it. That look. Oh, that look. The little slings and arrows. We stuff them away.

But they add up. And then, one day, we feel the weight.

November 23, 2022 6 Comments

Signs along the way

As you are going along The Way (and by The Way, I mean The Way of St. James, the Camino de Santiago), you see signs. Some are obvious. They boldly announce that you are on the right path. Or they unmistakably point you in the direction you need to take.

On the Camino these can be big, brilliant yellow arrows, or turquoise blue signs with canary yellow clamshells, or concrete waymarkers with kilometer counts. Sometimes these signs are eye-level and hard to miss. Sometimes they are painted on the sides of barns or fences or stone walls, faded, barely visible. Sometimes they are little plaques embedded in the road, easy to miss unless you are looking down.

Sometimes, especially in Galicia, these signs greet you so often that you stop seeing them. Other times you can go a long way without seeing a sign, and you are concerned that you have lost the way, and just as that concern is about to turn to worry or even into something darker, you see a sign. The relief borders on exaltation.

Sometimes, especially in Galicia, these signs greet you so often that you stop seeing them. Other times you can go a long way without seeing a sign, and you are concerned that you have lost the way, and just as that concern is about to turn to worry or even into something darker, you see a sign. The relief borders on exaltation.

And then there are the times you see no sign at all, but you see a person walking way ahead on the road, or you see the light of their head lamp. Although you may never catch up, never know who this person is, you feel gratitude and friendship. This happened to me along the Camino a number of times when I started alone in the pre-dawn hours. It brought to mind that E.L. Doctorow quote I am so fond of that I have used it in just about every talk I’ve ever given about the process of writing: “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

And that, really, is how I made my way: from sign to sign, by the light of my head lamp, by the distant light of someone else’s. Seeing just what needed to be seen to take the next step.

Now two weeks home, I am thinking: I wish life was like the Camino and every so often, just when you needed it, there was a sign to tell you, to reassure you, that you were on the right path. And then I think: Maybe life is like this, but we don’t know what the signs are, or we ignore the signs, or we are just looking elsewhere.

November 16, 2022 15 Comments

The Way

In two days I will begin making my way on The Way. That’s the Way of St. James, a network of 1000-year-old Christian Pilgrimage routes that starts at the foothills of the Pyrenees in St. Jean Pied-de-Port and ends at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, where the remains of St. James are enshrined. Probably not his skull bones. (He was beheaded in Jerusalem by King Herod in 44AD.)

The hiking/ walking route meanders through high mountains and deep valleys, undulating plains, vast olive groves, the Basque country, the vineyards of Rioja, the Meseta flatlands, the green rolling hills of Galacia. Small villages dot the landscape. Very occasionally there is a town of some size, notably Pamplona (of Hemingway and bull-running fame). If this sounds like I know what I’m talking about, I don’t. I am parroting brochure language. But soon I will know. For the next 30-40 days I will live this, hiking through it, seeing what I have never seen before, meeting fellow travelers, eating communal meals (and tapas at every opportunity), sleeping in rooms with bunk beds next to snoring, farting strangers. And get up the next morning and do it again.

When I have told friends that I would be doing this, I encountered two reactions. The first “oh this is on my bucket list!” I don’t have a bucket list. I don’t like the whole notion of a bucket list. But if I did have a bucket list, the Camino would not have been on it. I knew zero about the Camino—I mean I didn’t know of its existence—until I crossed paths two years ago with the documentarian Lydia Smith, director of “Walking the Camino.” It’s a beautiful film. I watched it (as you should too) and didn’t think about the Camino again until after Tom died. Then it occurred to me that this journey was just the kind of deep, immersive, solitary adventure I needed and wanted. Also, Tom never ever in a godzillion years would have wanted to do this. So I would not have to bear any “I wish he were here to share this” thoughts.

The second reaction when I told friends I was going off on this adventure was: “You’re going to write about this, right?” Well, that is what I do. So yes, I am. But in what way, in what form, I do not know. I will find my Way.

September 21, 2022 7 Comments

Resilience

You trip over a fallen log and gash open your leg on a spiky branch. And by “you” I mean me. And the wound is cleaned and stitched, and you heal. You’ll have a scar but big deal. The body is resilient. The body knows what to do. Would you have healed faster when you were younger? Yes. It is true. The older we are, the slower we heal. Physically.

Or you go for a long run or a hard hike. And by “you” I mean me. And maybe the next morning you feel it. So you’ll be a little sore. Big deal. The body is resilient. The body knows what to do. Would you have recovered faster when you were younger. Yes, it is true. The older we are, the longer it takes to bounce back.

But there is a kind of recovery that grows stronger with age, and it is more important than physical mending. It is emotional resilience. It is the ability to cope with and respond to setbacks and challenges, to unwelcome changes, to losses. To, you know, Life with a capital L.

When I was thirteen, Myles Cooley, my first boyfriend, my first love, the first boy I kissed, dumped me. I was devastated in a way I still remember. My heart ached. I cried. Every song on the radio was about love. So I cried some more. At that age, I had zero tools in my emotional resilience toolbox. I thought about him for years, yes years, afterward. I did not give my heart away (as a teen girl would put it) until I met my college boyfriend five years later.

But time and circumstance are good teachers. You learn. And by “you” I mean me. You develop problem-solving skills. You acquire coping strategies. You learn how to manage your emotions. You nurture what psychologists call an internal locus of control, that powerful belief that your actions can affect the outcome of events. This imbues you with a sense of confidence and control. You learn that you are a survivor.

You didn’t know any of this when you were thirteen.

Now you do.

And, although there is toughness that comes from this learning, there is also buoyancy.

Photo (mine): Madrone bark, Lithia park, Ashland

September 14, 2022 1 Comment

The stories we need to hear

Catherine Jones is smart, articulate, vibrant, passionate—and was the youngest person ever to be tried as an adult for murder. She was 13. Now in her mid-30s, the mother of two beaming, high-energy toddlers, she is the co-director of Outreach and Partnership Development at Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a national nonprofit that leads efforts to ban extreme sentences for children.

Arnoldo Ruiz is open-hearted and resolute, a compassionate listener, a tireless advocate for his community, and a devoted father. First arrested at fifteen, he bounced around the youth detention system until, at 18, he began serving a two-decade sentence in a maximum security prison. Today he is the program manager for the Youth Empowerment & Violence Prevention Department at Latino Network, working with at-risk Latinx youth and their families.

Sterling Cunio is a dynamo, as gentle and empathetic as he is powerful and compelling. Incarcerated at sixteen, he spent the next 28 years in prison. He is now an advocate, organizer and storyteller with Church in the Park, a nonprofit that works with the unhoused to restore dignity, relieve hunger, and increase awareness and understanding in the larger community. He also works part-time for the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at Lewis and Clark College Law School.

Richard Mireles is dynamic, expressive, optimistic, hard-working—and an ex-felon who spent 21 years behind bars. He is now the director of Outreach and Engagement at CROP (Creating Restorative Opportunities and Programs), a California nonprofit whose mission is to reimagine reentry through a holistic, human-centered approach to advocacy, housing, and the future of work. He is the host of the Prison Post Podcast, which is focused on stories of life after incarceration and what success looks like in reentry.

These are people we need to hear about. These are the stories that need telling. More than 600,000 men and women are released from prison every year. Mostly what we hear about them—when we hear anything at all—is how many quickly return to prison. (Please read my Myth of the Math of Recidivism post.) What we need to hear about is those who make it. Making it is a major accomplishment given the structural and deeply imbedded obstacles they face, the twisted and rocky road from caged to free. These four I write about here are not just making it; they are devoting their working lives, their prodigious energy, their hearts and minds to helping ensure that others have an easier path than they have had.

They know they can never undo the harm they did. But they can try to live a life of meaning and purpose.

Photo: Dusk from my front porch

September 7, 2022 2 Comments

Numbing numbers/ Action items

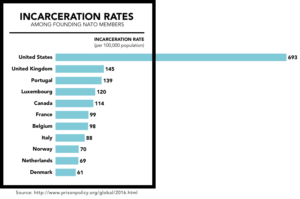

Not only does the U.S. have the highest incarceration rate in the world; every single U.S. state incarcerates more people per capita than virtually any independent democracy on earth.

One in 7 people in US prisons (203,865) is serving a life sentence. This is more than the entire incarcerated population in 1970.

In California, it costs $106,131 a year to incarcerate an inmate.

New York City spends $556,539 to incarcerate one person for a full year, or $1,525 per day.

K-12 schools spend an average of $13,185 per pupil annually.

It costs the taxpayers of Texas $2.3 million to execute one person.

There are currently 199 people on Death Row in Texas. There are 2,436 people on Death Row in the US.

These are numbing numbers. They can also be action items.

Here is a list of prison reform organizations you can read about, support, and join.

August 31, 2022 2 Comments

Harm and Punishment…and harm

There is a difference between punishing someone for doing harm and harming them in the punishment.

I don’t mean the Hammurabian “eye for an eye” kind of punishment, which obviously inflicts grievous harm—and is meant to. Or any of the punishments humans have invented to kill other humans: burning at the stake, crucifixion, impalement, beheading, drowning, hanging, defenestrating. The list, unfortunately, is much longer than this. And more grisly.

No, I mean the punishment we dole out today to those who do harm. We, the United States, a rational, post-Enlightenment culture with a heritage of social norms, ethical values and empirical beliefs systems. We, the United States, a country believed to be, by more than 50 percent of its citizens, “the greatest country on earth.”

We punish people by removing them from society, from their communities and their families, by taking away their freedom. This is certainly humane compared to slicing off their head or throwing them out a window (that’s what defenestration is). But we don’t just sequester them from society so that they can do no further harm. We put them in cages. We depersonalize them. We take away their ability to make meaningful (or really any) decisions. We create an environment that breeds and reenforces violence and distrust. We create a dangerous, toxic, sealed-off world that, over time, traumatizes. That scars the soul.

The punishment itself, the caging and deprivation, is not designed to rehabilitate. It is designed to inflict harm.

Okay, you say, these people DID harm, Let’s do harm back to them. But here’s the thing: If the punishment creates emotionally and psychologically damaged people who have become accustomed to being treated as sub-human and have come to think of themselves as such, what exactly are we accomplishing? If hyper-alertness, distrust and helplessness become the stuff of everyday life, how is this punishment helping to create people we want to see back in our communities?

Ninety-five percent of those we incarcerate are eventually released. What harm has been done to them during those years—often decades—they spent inside? What if the punishment causes lasting harm, not just for the individual but for all of us?

When you read the reentry stories in Free: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home you will see what it takes to transform the trauma of long-time incarceration into a well-lived life.

August 24, 2022 1 Comment

Costly, ineffective, unfair

“The current system of mass incarceration is costly, ineffective, unfair, racially discriminatory, socially destructive and legally infirm.” That is Robert N. Weiner talking, a Washington, D.C. lawyer and legal strategist, as he introduces the American Bar Association’s 10 Principles on Reducing Mass Incarceration. He is stating facts not opinions..

Costly? Total U.S. government expenses on public prisons and jails: $80.7 billion. On private prisons and jails: $3.9 billion

Ineffective? The U.S. Department of Justice itself states: “sending an individual convicted of a crime to prison isn’t a very effective way to deter crime.”

Unfair and discriminatory? Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at nearly five times the rate of whites, and Latinx people are 1.3 times as likely to be incarcerated than non-Latinx whites.

Socially destructive? As researcher and sociologist Bruce Western writes: “America’s prisons and jails have produced a … group of social outcasts who are joined by the shared experience of incarceration, crime, poverty, racial minority, and low education. As an outcast group, the men and women in our penal institutions have little access to the social mobility available to the mainstream. Social and economic disadvantage, crystallizing in penal confinement, is sustained over the life course and transmitted from one generation to the next. This is a profound institutionalized inequality that has renewed race and class disadvantage.”

Legally infirm? Mr. Weiner is one of the premier legal minds in the country. He ought to know.

At the American Bar Association’s annual meeting in Chicago earlier this month, the House of Delegates passed a resolution to adopt these 10 Principles. These are not radical ideas. They are thoughtfully considered, sensible, humane—and evidence-based. Prison reformers and social justice warriors have been highlighted all these and more for decades. It is notable that the mighty and powerful ABA is now taking this stand.

Limit the use of pretrial detention.

Increase the use of diversion programs and other alternatives to prosecution and incarceration.

Abolish mandatory minimum sentences.

Expand the use of probation, community release and other alternatives to incarceration, and create the fewest restrictions possible while promoting rehabilitation and protecting public safety.

End incarceration for the failure to pay fines or fees without first holding an ability-to-pay hearing and finding that a failure to pay was willful.

Adopt “second look” policies that require regular review and, if appropriate, reduction of lengthy sentences.

Broaden opportunities for incarcerated individuals to reduce their sentences for positive behavior or completing educational, training or rehabilitative programs.

Increase opportunities for incarcerated individuals to obtain compassionate release.

Evaluate the effectiveness of prosecutors based on their impact on public safety and not their number of convictions.

Evaluate the effectiveness of probation and parole officers based on their success in helping probationers and parolees and not their revocation rates.

August 17, 2022 No Comments