Category — Politics

Any reform is good reform. But.

Politicians are finally talking about prison reform. So yay for that. But what are they talking about?

Beto O’Rouke, Amy Klobuchar and Cory Booker have focused on ways to reduce our 2.3 million prison population by reforming drug laws and drug sentencing. Great. But it’s a myth that millions of people are behind bars for low-level, nonviolent drug offenses and that finding other ways of dealing with these offenses would solve our incarceration crisis. Eighty percent of those in prison are not there for low-level, nonviolent drug offenses. They are behind bars for committing violent crimes.

Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders want to eliminate private prisons. Yes, good idea. But that accounts for only 8.4 percent of the incarcerated population.

President Trump’s much heralded First Step Act reform bill resulted in the early release of 3,000 federal prisoners (with already impressive good behavior records). Good. But that’s .001 percent of the prison population. And, in case you didn’t know, 90 percent of U.S. prisoners are in state prisons not federal penitentiaries.

Any reform is good reform.

But this all feels like that cliché: rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

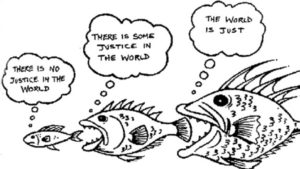

What we desperately need to do is rethink our entire notions of “punishment.” Yes, we need to hold people accountable for doing harm. But is our current system of incarceration the way to do this? We sentence people to very long prison terms (far longer than other western countries). The conditions in which they live are harsh, toxic, unhealthy, rob them of any decision-making power and teach them to trust no one.

If this system of punishment worked, that might be one thing. But within three years of release, about two-thirds (67.8 percent) of released prisoners are rearrested. Within five years of release, about three-quarters (76.6 percent) of released prisoners are rearrested.

Real prison reform needs to deal with not just the proven, well documented failure of our current system but with our own attitudes towards those who do harm, sometimes very serious harm. We need to ask ourselves tough questions: Are people who do bad things “redeemable”? Can they change? How should they be made accountable? How much punishment is enough? Given that 95 percent of those we put behind bars return (at least for a time) to their communities, how can we create a system that helps them become good citizens? Think on it.

September 25, 2019 No Comments

Who are we?

We do not hate each other.

We are not warring tribes.

We are mostly decent people. Yes we are. And we mostly want the same things in life. Yes we do.

I know it doesn’t feel like that. I know that it seems there is vitriol and hostility everywhere, that evil prevails, that conflict is the norm. I have a few things to say about that.

There’s a journalistic axiom: When a dog bites a man, it’s not news. When a man bites a dog, that’s news. In other words: What makes the news is the unusual event, the oddity. The one car crash during rush hour, not the tens of thousands of commuters who make it home safely. The one distraught mother who harms her baby, not the millions who love and protect their children.

Before media streamed, drowning us in 24/7 content, before we carried the world in our pockets, back when tweets were what birds did, those who studied news content and journalism’s “man bites dog” proclivities discovered what they called the Mean World Syndrome. When asked about crime, when questioned about their personal safety and the health of their communities, people vastly overestimated trouble. They thought crime was far more prevalent than it was. They believed their chances of being a victim were far in excess of reality.

I think we are suffering right now from a version of Mean World Syndrome brought on by the masterful cooptation of the news cycle by the nastiest, meanest in our midst, aided and abetted by our bloated media diets, and sharpened by our ignorance of how real people really live.

I don’t claim to be an expert on how real people really live. But I know a lot more now than I did before my husband and I went on two camping trips that criss-crossed America (first coast to coast, then border to border) and brought us face-to-face with places and people in the massive “fly-over” zones that make up most of our country. We stuck to two-lane highways, spent time in towns you never heard of, ate breakfasts in diners, chatted up postmistresses and state park workers, waitresses and grocery clerks, people whose families had lived in the same towns for generations.

For these past 12 days, on this latest trip from the Canadian to the Mexican border down the country’s middle on Route 83, I experienced the country not via my news feed but through personal interactions. And I was heartened by what I saw and heard, by the Black, white and brown kids playing together in the school yard, by the blended Anglo-Mexican families picnicking, by friendly greetings on the street, by the everydayness of life lived in communities that are well loved by the people—the diverse people—who make these places their home. (Read this New York times piece about rural America.)

September 18, 2019 3 Comments

Education behind bars

Prison inmates are among the least-educated people in America.

About 40 percent haven’t graduated from high school. (In some states and with certain populations, the number is much, much higher—as high as 80 percent.)

In prison, one of the most effective rehabilitation tools is…that’s right: education. Research, and lots of it, shows that educational opportunities and achievement behind bars keep people from coming back to prison. (95 percent of all prisoners are eventually released. Within 5 years, 75 percent of them are back in jail.) If you release someone with the same skills with which they came in, they’re going to get involved in the same activities as they did before.

It’s not “just” the acquisition of skills that makes learning opportunities in prison a good idea. It is the experience of being in a stimulating environment, of taking part in spirited discussion, of learning to think critically, of reading, of exposure to new ideas. Education does far more than make a person more employable. It makes a person curious, engaged, thoughtful, able to question and analyze. It promotes understanding of the “other.” It allows people to view their lives in context. And, yes, it is statistically proven to prevent recidivism.

So education should be a cornerstone of programming in prison, right?

Of course.

But so very little money is spent on any programming in prison–approximately 6 percent of corrections spending is used to pay for all prison programming—that educational opportunities are sparse. (There are notable, exceptionable programs like Hudson Link, the Education Justice Program, and the Bard Prison Initiative.)

It’s been said that offering classes to inmates is being “soft on crime.” But if getting an education makes it far more likely that a released felon can make a decent, non-criminal life, then offering classes inside is actually being TOUGH on crime. It prevents future crime.

We have an incarceration crisis. We have a re-entry crisis. Everyone, regardless of politics, agrees. In-prison education can help. So can reversing the 1994 ban on allowing inmates to apply for Pell grants that make education affordable to low-income students.

We hear only about the grim life behind bars, the violence, the drugs, the gangs. But there is something else going on. There is a real hunger to learn, to read and talk, to reach beyond the bars and walls, to imagine a new life. I know this first hand. I work with a group of long-incarcerated inmates at a maximum security prison. We read, we write, we talk about the power of stories to change lives. It is not a formal class. But it is education. And I think—actually, I am convinced—it is making a difference.

May 8, 2019 1 Comment

America the Beautiful

It is such a pleasure, such a relief (and yes, I know, such a privilege) to be enveloped by warm feelings about my country. I don’t, of course, mean the current government. I don’t, of course, mean the heart-stopping (sometimes literally) inequities, the deep and damaging social issues that ruin lives and erode spirits.

It is such a pleasure, such a relief (and yes, I know, such a privilege) to be enveloped by warm feelings about my country. I don’t, of course, mean the current government. I don’t, of course, mean the heart-stopping (sometimes literally) inequities, the deep and damaging social issues that ruin lives and erode spirits.

I mean the geography. I mean the Petrified Forest with its mineralized, crystalline logs—blue, green, pink, orange—part of a striking desert landscape that used to be lush tropics. That was millions of years ago when all the continents were one land mass, Pangea, when Arizona was where Costa Rica is today. I mean the otherworldly formations of blue-gray bentonite clay, striated hillocks and mesas with eroded surfaces that look like elephant skin. I mean escarpments that rise from the flat scrublands and extend for miles. Rock outcroppings, arches, table-tops, cairns, canyons and cliffs. I mean pinon forests, juniper, Ponderosa pine. I mean 9,000-foot mountain passes and 12,000-foot mountains.

And I also mean the richness of cultures that live in these places: the silver-and-turquoise-jeweled arty types walking the streets of Santa Fe, the motorcycle-riding day drinkers in Madrid (pronounced MAY-drid), the New Agers soaking in Giggling Springs up at Jemez, the pick-up driving cowboys of Gallup—white, Hispanic, Native—in their straw hats and billed caps, the families—Native and Hispanic, the old people with their faces etched by sun and wind sitting beside grandchildren, great grandchildren.

This is the land that used to be Mexico. This is the land that used to be Navajo and Hopi, Zuni and Apache. And “we”—the U.S.A. of the 18th and 19th and 20th centuries—took it by force, by disease, by deceit, by political maneuverings. That is our history. That is our shame.

But it is also true that when you drive through this country, hike it, walk its main streets, eat at its diners, you can see how deeply and permanently embedded our diversity really is. The Navajo are here, 65,000 people strong. Almost fifty percent of New Mexicans are either descendants of Spanish colonists or recent immigrants from Hispanic America. For just a moment, let’s not talk about poverty here. Let’s revel in the beauty of geographic, cultural and racial diversity. There is a deep pleasure in experiencing it, in walking through it. Land and people.

March 13, 2019 2 Comments

Our President

Fool, oaf, clown, dunce, dolt, dullard, ignoramus, nitwit, dimwit.

Fathead, blockhead, numbskull, dunderhead, meathead, bonehead, chucklehead, knucklehead.

Lamebrain, peabrain, birdbrain, pinhead, clot, twit, dope, jackass, clod, donkey, bozo.

Our president.

A thoughtless, careless, man whose ignorance about democracy, about government, about history, about this country is astonishing.

A cruel, stupid, impulsive man whose ignorance about the planet and our future is mind-boggling.

A pig of a man who treats no one with respect. And brags about it.

A disgrace.

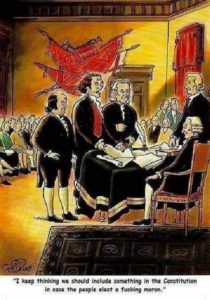

Those who crafted the Constitution did, in fact, consider the idea that we might some day elect such a person.

The Constitution, Article II, Section 4:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

(Written on Presidents’ Day)

February 20, 2019 1 Comment

Privilege

For a long time, the fact that I was female blinded me to the fact that I was privileged.

At my high school, the boys had a football team, a basketball team, a soccer team, a baseball team, a wrestling team, a lacrosse team, a cross-country team, a tennis team, a bowling team, and a fencing team.

The girls had tennis.

I played tennis.

At the end of each year, the boys had a banquet to honor the athletes. Every boy who played on a varsity team was awarded a big felt letter to be sewn (by a mother) on the back of his letterman jacket. The girls’ tennis team didn’t have banquets or jackets. (In fact, we didn’t have uniforms; we supplied our own tennis balls; our mothers drove us to matches.) At the end of my senior year, I was handed a small envelope in which was a quarter-inch-high black letter L, the first initial of my high school. It was a charm for a charm bracelet. I didn’t own a charm bracelet.

I felt no privilege when I was mugged from behind a half a block from my apartment in Chicago, when I had to run from a group of teenage boys on the streets of Seattle, when men I hardly knew felt they could reach out and touch my pregnant belly, when a man who made “overtures” that I ignored and later became my boss took pleasure out of thwarting my efforts in the workplace.

But then I met B who, at 13, was abandoned by her mother on the streets of Portland and had only her body and her wits to support herself, whose street life led to drugs, whose drug life led to crime, whose criminal life led to prison. And I thought about the privilege of a stable home.

And then I met P, a mother at 15, herself the child of a teen mother, working the only kind of job she’d ever have: minimum wage, no benefits. I met her 14-year-old grandchild who had just dropped out of school and was headed down the same path as her mother and grandmother. And I thought about the privilege of being born into the middle class.

And then I met H, like me a third-generation American, who has been asked, her whole life, “where are you from?” And when she answers “Denver,” they look at her suspiciously and say, “No, I mean, where are you really from?” And I thought about the privilege of having a white face.

And then I met D and learned of an adolescence scarred by bullying and abuse. And thought of the privilege of my hetereosexuality.

The thing about privilege is that you can be ignorant of it, or you can deny it. You can—as we’re seeing in Trump Era America—embrace it, parade it and employ it as a bludgeon.

You can see it, be an armchair liberal and feel guilty about it.

Or you can use your privilege to help end your privilege.

January 23, 2019 2 Comments

Happy Mentorship Month

January is National Mentor Month!

And I get to celebrate. I am an “official” mentor through Sponsors Mentorship, an exceptional program that matches community members with those recently released from prison. This simple, person-to-person, let’s-have-a-cup-of-coffee, let’s-take-a-hike relationship is, in Sponsors’ words, “an affirmation of the belief that there’s no such thing as a throw-away person.”

Re-entry into the “real world” is extraordinarily challenging for those who have been behind bars, especially those incarcerated for many years, even decades. Re-entry goes far beyond the definable challenges of finding housing, finding employment, meeting probation provisions, staying clean and sober. It means, for those away for decades, entering a new world, a swipe and click world they know nothing about, a world of people walking around staring at hand-held devices they have never held in their hands that perform functions they didn’t even know existed.

But the underlying challenge of re-entry is even more formidable. It is learning how to unlearn the institutionalized self. That’s the persona, the attitude, the language–verbal and body—the way of relating, of being, that an imprisoned person adopts to stay sane and safe. It is functional behind bars. It is dysfunctional in the world outside.

My new book, coming out in May, A Grip of Time: When Prison is Your Life, is about what life is like when that life is lived almost entirely behind bars. It is what it takes to live a life of meaning in a place devoid of meaning. It is about guilt and shame and the possibility of change and forgiveness. (It’s also sometimes funny. Really.) The book is based on my three years of facilitating a writing group for Lifers at a maximum security penitentiary, working with men convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. I teach them how to craft stories about their lives. They teach me much bigger lessons about hope and fear and trust, about what matters and what doesn’t. To learn so much about life from those who live such a constricted version of it is an extraordinary experience.

My next book will be about re-entry–thus my new involvement with Sponsors. Ninety-five percent of the men and women we imprison will be released someday. Last year more than 650,000 were, including my mentee. I am learning from her what re-entering the world means. I am learning from the compassionate, clear-eyed, deeply empathetic but completely professional people at Sponsors what it takes to make successful re-entry possible. The Mentorship Program is one small part.

January 9, 2019 4 Comments

Sisterhood is powerful

Sisterhood is Powerful, the book, was the first comprehensive collection of writings from second-wave feminism. Cited by the New York Public Library as “one of the 100 most influential books of the 20th century,” it was edited by Robin Morgan, one of the founders of what was then called the Women’s Liberation Movement. She continues to be an international voice for women’s empowerment, a forever kickass feminist, an in-it-for-the-long haul force of nature.

I’m referencing her today because of her recent long, impassioned, full-of-empowering facts blog about the mid-term election “Blue Wave” and how women surfed it.

For those of us who bit our nails to the quick last Tuesday night, hoping for a tidal wave that would submerge (okay, drown) those who currently have a stranglehold on our country, there were some disappointments. We wanted the Senate AND the House. We wanted Claire McCaskill. We wanted Heidi Heitkamp. Stacy Abrams. But we barely had time to consider what we had won before the hate-mongerer in the White House did his usual “no, look over here” trick of waylaying the media and our attention.

Robin’s blog reminds us to revel in the victories of the 2018 midterm, especially as they relate to women. (Here are other reports about this historic moment.)

Consider that 256 women were candidates for the U.S. House or the U.S. Senate in the general election—a record-breaking number–and as of Nov. 13, 114 were victorious. That includes the Arizona Senate race, in which U.S. Rep. Kyrsten Sinema was declared the winner on Monday. The 116th Congress will see the largest class of female lawmakers ever. (And the number may grow as several House races have still not been called.)

And the women elected are a diverse group. There are two Muslim women, two native Americans, and two Latinas. In all, Robin reports that 42 women of color were elected, and “at least” three lesbians. There are new female members from the red states of Kansas, Iowa, Florida, Texas, Georgia and Oklahoma.

Wow. Just wow.

Also, Robin reminds us that a record number of women ran for state legislatures–3,388 —and according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, more women will serve in state legislatures come January than at any point in American history.

Sisterhood is indeed powerful.

November 14, 2018 No Comments

#iadoregon

I know.

Oregon—that’s us on your upper left, you know, above California—is of no great electoral import. In a presidential year, if we go blue (and we go blue), no one cares. Seven measly votes.

We have five members in the House of Representatives, four people who care about the welfare of the state’s citizens and one who voted to take away health care. All five, all incumbents (four Democrats, one Republican) won reelection. So did our Democratic governor, Kate Brown.

I am so very proud to be an Oregonian this post-election day. And it’s not only because of the election results I mention above. It’s because of how my fellow citizens voted on several of the initiatives on the ballot. These victories or defeats speak to our values, our principles and our character. I’m going to mention two. But first, to brag some more about Oregon: We are the originators of the Initiative and Referendum (a Progressive Era reform). You’re welcome.

Oregonians defeated an initiative to take away state funding for abortions. If passed, it would have meant that reproductive freedom and choice would be reserved for those who could afford it.

Oregonians defeated a specious initiative that would have created a constitutional amendment to ban the taxing of groceries. We don’t tax groceries. We do not have a sales tax. But still…sounds good, right? With the amendment our groceries can never be taxed! Vote yes!

But Oregonians were savvy enough to see through this sugary-drink-company funded initiative. Soda is considered a “grocery.” There is a national move to tax soda. It has no nutritional value and is implicated in a myriad of health problems (not to mention dental issues). If this innocent-sounding, protect-us-from-being-taxed on broccoli-and-bread initiative had passed, there could never be a (well deserved) “sin” tax on soda.

Our state motto: Alis volat propriis which translates as “She flies with her own wings.”

And she does.

November 7, 2018 1 Comment

Immigrants All

“We are come to rest and push our roots more deeply by the year.

But we cannot push away the heritage

of having been once all strangers in the land;

we cannot forget the experience of having been all rootless, adrift.

Building our own nests now in our tiredness of the transient,

we will not deny our past as a people in motion

and will find still a place in our lives for the values of flight.

This is from historian Oscar Handlin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Uprooted, a deeply researched and deeply felt book that chronicles “the great migration that made the American People,” Handlin was born in Brooklyn to Russian immigrant parents, went to Brooklyn College and then Harvard, where he became a professor.

At this moment of purposeful ignorance about our history as a country of immigrants, at this moment of fear of the other, it is important to remember that, once, we were all “The Other.”

Between 1880 and 1920, 23 million immigrants arrived in the US. They were fleeing crop failures and famine, political and religious persecution, war. Between 1525 and 1866, 12.5 million Africans were stolen from their homes and shipped to the New World. We were once all strangers in this land.

After World War II, the European refugee crisis was all consuming. This is how President Truman responded: “I urge the Congress to turn its attention to this world problem in an effort to find ways whereby we can fulfill our responsibilities to these thousands of homeless and suffering refugees of all faiths.”

The photo is of my paternal grandparents, European refugees who came through Ellis Island in the early years of the 20th century.

October 31, 2018 3 Comments